Why the Gulf States Turned on Lebanon

Saudi Arabia and its allies are pressuring Lebanon to gain leverage in Syria and Yemen.

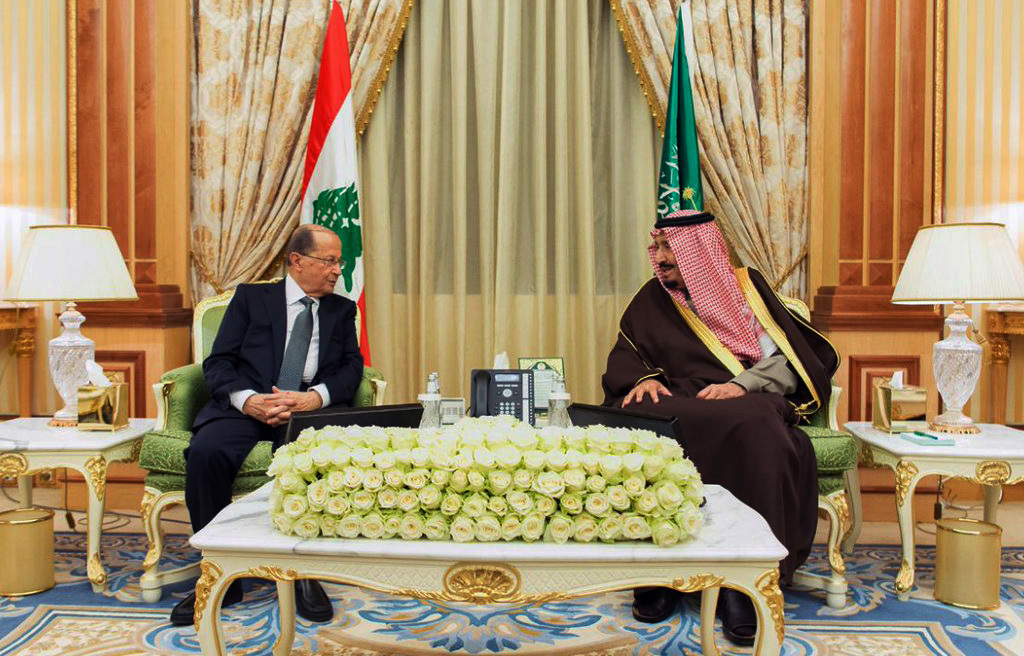

In recent weeks, many of the Gulf Cooperation Council states have ostracized Lebanon, initiating what may even be a developing boycott. In early November, Saudi Arabia withdrew its ambassador from Beirut and ordered the Lebanese ambassador to leave Riyadh. Saudi companies were ordered to halt all dealings with Lebanese firms, and Lebanese imports are now banned in the kingdom. The United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and Kuwait followed suit by withdrawing and expelling diplomats. The most severe measures – holds on remittances from Lebanese expatriates in the Gulf, total travel bans, and a thoroughgoing disinvestment from the Lebanese economy – have yet to be imposed. However, it is clear that most of the Gulf states are not only unwilling to help revive the cash-strapped and foundering Lebanese state and economy, they are taking an unprecedented stance to isolate Lebanon, which is likely to exacerbate its woes.

The ostensible reason has been a series of provocative and hostile remarks by various Lebanese officials and prominent figures aimed at Gulf states and their policies. Yet these provocations are better understood as a final straw than the actual proximate cause for the isolation campaign. Had relations been better, or had Gulf countries perceived continued opportunities through engagement with Lebanon, specific individuals or groups could have been targeted for sanctions rather than the entire country, or the entire affair could have been waved away or answered rhetorically. Instead, the reaction appears disproportionate because it is not primarily motivated by the insults themselves but rather by the underlying conditions they may have highlighted.

The Underlying Causes

The de facto abandonment of Lebanon by most of the Gulf states has been developing for at least a decade. These countries have long been uneasy with the decisive political power in Lebanon of the pro-Iranian Shia group Hezbollah. Those concerns have been steadily mounting along with the rise of Iran’s regional influence and reach following the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq and the successful intervention by Russia, Hezbollah, and Iran in the Syrian civil war beginning in 2015 in support of the Damascus regime. Since the main part of the Syrian conflict has ended with the fall of Aleppo to pro-regime forces, Hezbollah has come to occupy a regional role far beyond its function as a Lebanese political party and militia. It effectively serves as the vanguard of Iran’s extensive network of allied militia groups in Arab countries such as Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, Yemen, and beyond with a presence and effective role far beyond Lebanon’s borders.

After many years of pressure and efforts to find ways of maneuvering within Lebanon to offset or constrain Hezbollah’s activities and ability, many of the Gulf states have seemingly come to the conclusion that working inside Lebanon under current circumstances is a lost cause. The first clear sign that Gulf countries were prepared to walk away from Lebanon came in 2016, when Saudi Arabia cut billions of dollars in aid to the country, discouraged Saudi tourism to Lebanon, and, along with the full Arab League, formally designated Hezbollah a terrorist organization. Eventually some aid was resumed, but the level of support Riyadh was providing to its Lebanese allies, notably Sunni Muslim constituents around former Prime Minister Saad Hariri but also some Christian and Druze groups, remains drastically curtailed. After that, considerable aid to and trade with Lebanon had resumed until recently, but Gulf countries were no closer to garnering the influence to prevent the state and society they were underwriting from being used against their interests throughout the region.

This exasperation, coupled with the recent flurry of insults, is what has primarily motivated the ostracism of Lebanon. However, the broader regional context also plays a crucial role. The shift for at least the past 18 months throughout the Middle East by regional players away from direct or indirect confrontations to a reliance on diplomacy, politics, and commerce to pursue their interests helps to explain Gulf strategic thinking regarding Lebanon. In effect, closing the petrodollar ATM to the Lebanese, particularly at their moment of most extreme self-inflicted economic privation, is the diplomatic and commercial stick that is available when conflict and confrontation is no longer regarded as attractive.

Sticks as Well as Carrots in Regional Maneuvering

Most of the elements of maneuver, in this period of “consolidation, retrenchment, and maneuver” by regional actors, have taken the form of diplomatic and commercial outreach. New dialogues, rapprochements, and trade arrangements have proliferated in the Middle East, often to the surprise of many analysts who assumed intractable animosity between antagonists. Regional players have been generally trading in the exchange of carrots to entice each other into de-escalation and sometimes even various forms of cooperation. However, as the isolation of Lebanon demonstrates, diplomatic, political, and commercial maneuver also can involve sticks; Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, and Kuwait have given up on securing anything positive from direct engagement with Lebanon under current circumstances and sense that squeezing the Lebanese in this manner could provide leverage and new openings.

At the very least, they are convinced that this is no loss for them if none of it works out. The traditional Arab and Gulf affection for Lebanon as a cultural, educational, and commercial center, largely based on memories from the 1960s and ‘70s, has long faded. The rising generation of Gulf Arab leaders and citizens have little of the nostalgia for the heyday of Beirut that their parents and grandparents often cherished. To this younger cohort, Lebanon seems like a sinkhole of endless, wasted aid, and investment, likely in the tens of billions in the past decade, and a prime source of regional instability and Iranian mischief-making.

Moreover, compared to Syria and Iraq, Lebanon appears to be of secondary strategic importance at best. It is not coincidental that Lebanon is being cut adrift just as Gulf countries, led by the UAE, begin to reengage in Syria, looking for opportunities to work with Russia, Turkey, the United States, and even, potentially, the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad to sideline Iran’s and Hezbollah’s sway in Syria. To these Gulf countries, Lebanon is strategically important mainly as a geographic and political appendage of Syria. It also until recently served as a sanctions-busting financial hub for the Syrian regime and a base for rampant smuggling. The long-standing Sunni Arab nightmare has been of an Iranian-controlled military corridor or “crescent” leading from Iran through Iraq and Syria down into Lebanon and the Mediterranean coast. Many Arab governments believe developing such a secure passage between Iran and the Mediterranean is a primary geostrategic goal for Tehran. And although it has yet to be achieved, since 2003 it has gone from a far-fetched fantasy to a viable goal.

Syria, Lebanon, and Iran

Therefore, Syria, a far larger and, in the current view of most Gulf countries, a far more strategically and politically important Arab country, is the real subject of maneuver at present, along with Iraq. They see progress in Lebanon as more aptly attained through a long-term engagement in Syria. The ultimate aim is not just to marginalize the influence of Iran and Hezbollah inside Syria, it is to encourage the Syrian regime to move independently of Tehran to reestablish its own hegemony inside Lebanon, thereby curtailing Hezbollah’s control of the country. This may seem far-fetched under current circumstances. But given the history of Syrian sway in Lebanon, the wide-ranging network of allies and ties that Damascus has throughout the country, and its subdued but detectable yearning for restoration of its former powers (independent of Iranian domination) all suggest this might be a possibility.

In mid-September, Hezbollah insisted that its Maronite Christian allies in President Michel Aoun’s Free Patriotic Movement finally agree to the formation of a government, even though it didn’t meet the Free Patriotic Movement’s long-standing demands for a veto level of representation in the Cabinet. Hezbollah’s demand was driven in large part by the fear that Lebanon’s freefall was creating opportunities for other Arab countries, notably Syria, to begin to meddle again in Lebanon on the cheap and behind its back. Squeezing Lebanon therefore, for these Gulf countries, is a means of directly pressuring Hezbollah and, through it, Iran. Moreover, it could help, over the long run, to ease the path for Syria to become a competing (Arab), external force inside Lebanon. Again, if this does not pan out, current Gulf thinking suggests that at the very least nothing significant will have been lost.

Yemen and Iran

But above all, the explanation for the timing of the isolation of Lebanon may lie in the war in far-off Yemen, as well as the Saudi dialogues with the Houthis in Oman and Iranians in Iraq. For years, Saudi Arabia has been looking for a way to extricate itself from the quagmire in Yemen. Riyadh’s Yemeni allies associated with the United Nations-recognized government of President Abd Rabbu Mansour Hadi have proved remarkably ineffective, and the final major holdout to a thoroughgoing Houthi victory in northern Yemen is the country’s key economic center in Marib, which is currently under constant attack and appears liable to fall to the rebels.

Unlike the regional actors, all of which have turned away from conflict, many local Yemeni actors continue to search for battlefield victories to advance their domestic strategic positions. While Saudi Arabia seeks to extricate itself, the Houthis – anticipating continued military gains – see ongoing conflict as beneficial to their political, strategic, and negotiating positions. Hence the talks in Oman have been fruitless from a Saudi point of view.

Yet Riyadh lacks leverage over the Houthis and is seeking to use its dialogue with Iran in Iraq to try to aid its quest for an exit. For the Saudis, the Baghdad talks have been equally frustrating, as they seek to discuss Yemen while their Iranian counterparts focus entirely on the restoration of diplomatic ties. The talks continue not because of any shared agenda but because of a mutual desire for de-escalation.

Undoubtedly one of Riyadh’s primary calculations is that pressuring Tehran through Lebanon and Hezbollah suggests a quid pro quo, not only in terms of diplomatic relations in exchange for the easing of Iranian support for the Houthis, but also as a kind of Lebanon-Yemen exchange. The implicit subtext of the current situation is that, if Iran eases pressure on Saudi Arabia by curtailing support for the Houthis, Saudi Arabia and its allies could ease or at least not intensify their own pressure on Lebanon and hence on Hezbollah and ultimately Iran. The linkage is greatly underscored by the strong evidence of extensive Hezbollah support on the ground for the Houthis on the battlefield and in terms of technical, communication, and political expertise.

What If This Fails Again?

Ironically, then, Lebanon’s best hope for extrication from this sudden and painful Gulf pressure could be dependent on not only talks in Oman and Baghdad, to which it is not party, but even battlefield outcomes in distant Marib. If, however, in the medium term, this Gulf pressure campaign on Lebanon fails to yield any benefits with regard to Lebanon, Syria, Iran, or Yemen, it may have to be rethought. And the calculations that Lebanon is of little strategic importance and that the potential reintroduction of Syrian hegemony in Lebanon could benefit the Arab world both rely on numerous debatable assumptions. In the current era of maneuver and search for leverage, this move, however brutal to Lebanon, does have its identifiable logic for the Gulf countries. But it may well prove as fruitless as similar efforts in the past.

The views represented herein are the author's or speaker's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of AGSI, its staff, or its board of directors.