Murky Waters: Could Undersea Cable Vulnerabilities Cloud the Gulf’s AI Vision?

Undersea cables are necessary for the rapid movement of information that the Gulf’s AI ambitions require, but they are uniquely vulnerable to disruption and sabotage.

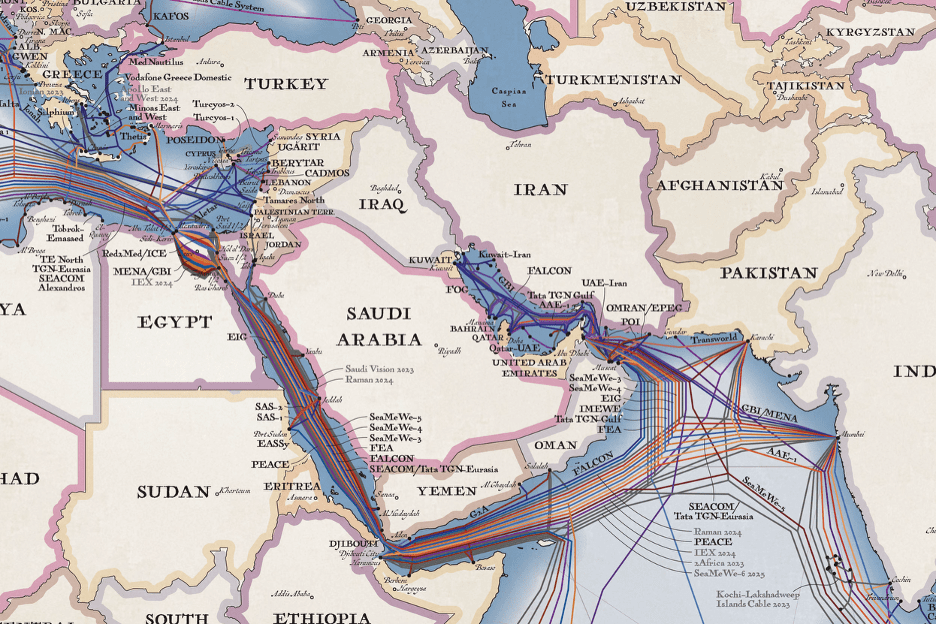

Undersea cables form the backbone of global digital connectivity, carrying more than 95% of international data traffic, including internet, phone, and financial transactions. They power the global economy and connect societies across continents with unmatched speed and capacity. Their importance lies in facilitating everyday digital life while underpinning global commerce, innovation, and international relations. Strategically, undersea cables are critical infrastructure for governments and businesses, making them both vital assets and vulnerable points in geopolitics and cybersecurity. As Gulf Arab countries move rapidly to establish themselves as global centers of investment and innovation in artificial intelligence, their ambitions depend on a uniquely vulnerable network of undersea cables.

Undersea Cables and AI

Undersea cables provide the high-capacity, low-latency global data transmission that underpins AI development and deployment. Training large AI models requires moving massive datasets among data centers, often across continents, and delivering AI services to end users depends on fast, reliable international connectivity. Undersea cables serve as the hidden physical infrastructure that links global compute resources, cloud providers, and users, making them as critical to the AI economy as data centers and advanced semiconductors. Meta, the parent company of Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp and the second-biggest driver of internet traffic, is investing in a new global fiber-optic subsea cable to meet the surging data demands driven by its growing use of AI.

Gulf countries have made AI central to their economic diversification and modernization agendas, investing heavily in data infrastructure, research, and regulation. Across the region, governments are channeling sovereign wealth funds into AI research centers, cloud computing, and Arabic-language models tailored to local needs. At the same time, they are modernizing public services and creating smart, AI-enabled cities in efforts to position the region to become a global AI hub.

Source: Telegeography

Exposing Vulnerabilities

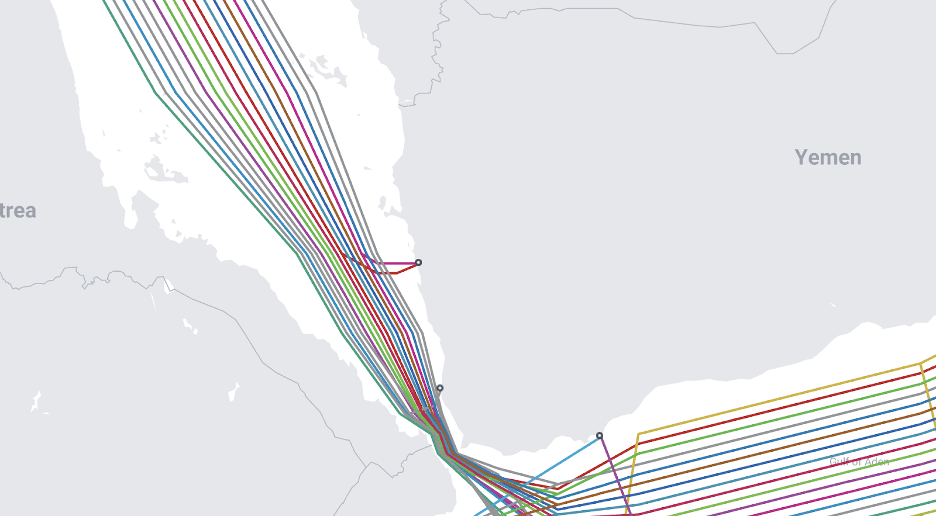

Around the Arabian Peninsula, undersea cables are under increasing strain from both physical damage and geopolitical risk. Several incidents involving undersea cables have highlighted growing concerns about sabotage, accidents, and hybrid warfare. In the Red Sea, in particular, major submarine cables have recently been severed causing internet slowdowns and higher latency across Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Pakistan, and India. Such disruptions have been blamed on ships dragging their anchors and possible militant activity, especially by Yemen’s Houthi rebels. Some of the breaks have coincided with maritime incidents: For example, in early 2024, the Belize-flagged Rubymar was struck by Houthi missiles and dragged its anchor across busy cable trenches before finally sinking, leading to unintentional damage to the cables.

The Red Sea area presents a particular challenge to undersea cable operations. Even before the start of Houthi attacks on merchant ships traversing this strategic chokepoint, Yemen’s war generated its own set of complications around the deployment and repair of undersea cables. The 2Africa cable, the longest undersea cable in the world, has largely been laid, but a significant length of cable that would lie in Yemeni waters is still missing. A similar challenge could be faced by other cables planned to line the Red Sea in coming years. There are also risks to ships deployed to repair damaged cables; they must remain stationary for days, making them particularly vulnerable to attacks.

However, this undersea cable vulnerability is not unique to the region. In northern Europe and the Baltic Sea region, there is growing suspicion of deliberate interference to undersea cables. Finland recently charged the crew of the tanker Eagle S with aggravated sabotage for dragging its anchor over and severing several undersea telecom and power cables between Finland and Estonia. Sweden is also investigating the suspected sabotage of cables in the Baltic Sea. In response, NATO has launched a mission to protect the region’s subsea infrastructure.

Overall, while many of the documented disruptions still appear to be accidental, the scale and clustering of recent events have raised alarms about the potential for intentional attacks or at least negligent damage that could have a severe impact.

Source: Telegeography

Creating Redundancies and Finding Alternatives

There are alternatives to undersea cables, but none yet match their speed and cost efficiency for supporting AI technology. Satellites, especially emerging low-Earth orbit constellations, such as Starlink, OneWeb, and Amazon’s Project Kuiper, can provide global coverage and redundancy, but their bandwidth is limited and latency is higher than with fiber-optic cables, making them useful mainly for remote or underserved areas. High-altitude platforms, such as stratospheric drones or balloons, remain experimental and not scalable for AI’s data demands. Terrestrial fiber networks and regional data centers can reduce reliance on long-haul cables by localizing compute resources, but global AI training and model distribution still depend on intercontinental connections. In the long run, new technology may offer complementary pathways, but undersea cables will remain the backbone of the AI economy for the foreseeable future.

Minimizing disruptions to undersea cables requires a mix of measures like building redundancy and route diversity so traffic can be rerouted quickly if a cable is cut, burying or armoring cables in shallow waters to reduce damage from anchors and fishing gear, and improving monitoring systems, such as using sensors, drones, and AI-enabled maritime surveillance to detect potential threats early. Already, regional governments and the private sector are undertaking a major push to expand subsea cable infrastructure in the region including “landing” stations and cables, improving redundancy, diversity of routes, and resilience. A new high-capacity undersea cable has linked the UAE and Kenya, marking the first direct digital link between the Gulf and the African continent. In January, Ooredoo, the Qatari multinational telecommunications provider signed an agreement to build a cable connecting seven countries in the region – Qatar, Oman, the UAE, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Iraq. More recently, Saudi Arabia and Syria have entered talks to build data cables connecting the kingdom to Europe through Syria’s SilkLink project, which would allow data to bypass the Red Sea.

Outside the Gulf, governments and companies are also investing in geopolitical safeguards, including international agreements and naval patrols to protect subsea infrastructure in high-risk zones, which could provide a blueprint for possible coordinated action among Gulf countries. NATO’s Maritime Centre for Security of Critical Undersea Infrastructure, launched in 2024, assists its Allied Maritime Command in protecting undersea energy pipelines and cables. Globally, the United Nation’s International Telecommunication Union recently established the International Advisory Body for Submarine Cable Resilience to enhance protection for undersea cables, bringing together experts from around the world from the public and private sectors, including representatives from submarine cable operators, telecommunications companies, and government agencies. Closer coordination among these parties can ensure faster repair times and better incident response. Finally, new technologies, such as satellite-based backups, inter-data-center caching, and regional AI model deployment can reduce the impact of outages by lessening reliance on any single cable route.

The views represented herein are the author's or speaker's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of AGSI, its staff, or its board of directors.