Facing sustained Israeli military threats since the June conflict and continued Western economic pressure, Iran is deepening its defense and economic ties with China. This shift is part of a broader foreign policy recalibration that includes expanded military cooperation and closer integration into China’s Eurasian economic initiatives. But Iran’s alignment with China is not just reactive – it is part of a deliberate, forward-looking strategy shaped by new threat perceptions and expectations of long-term estrangement from the West.

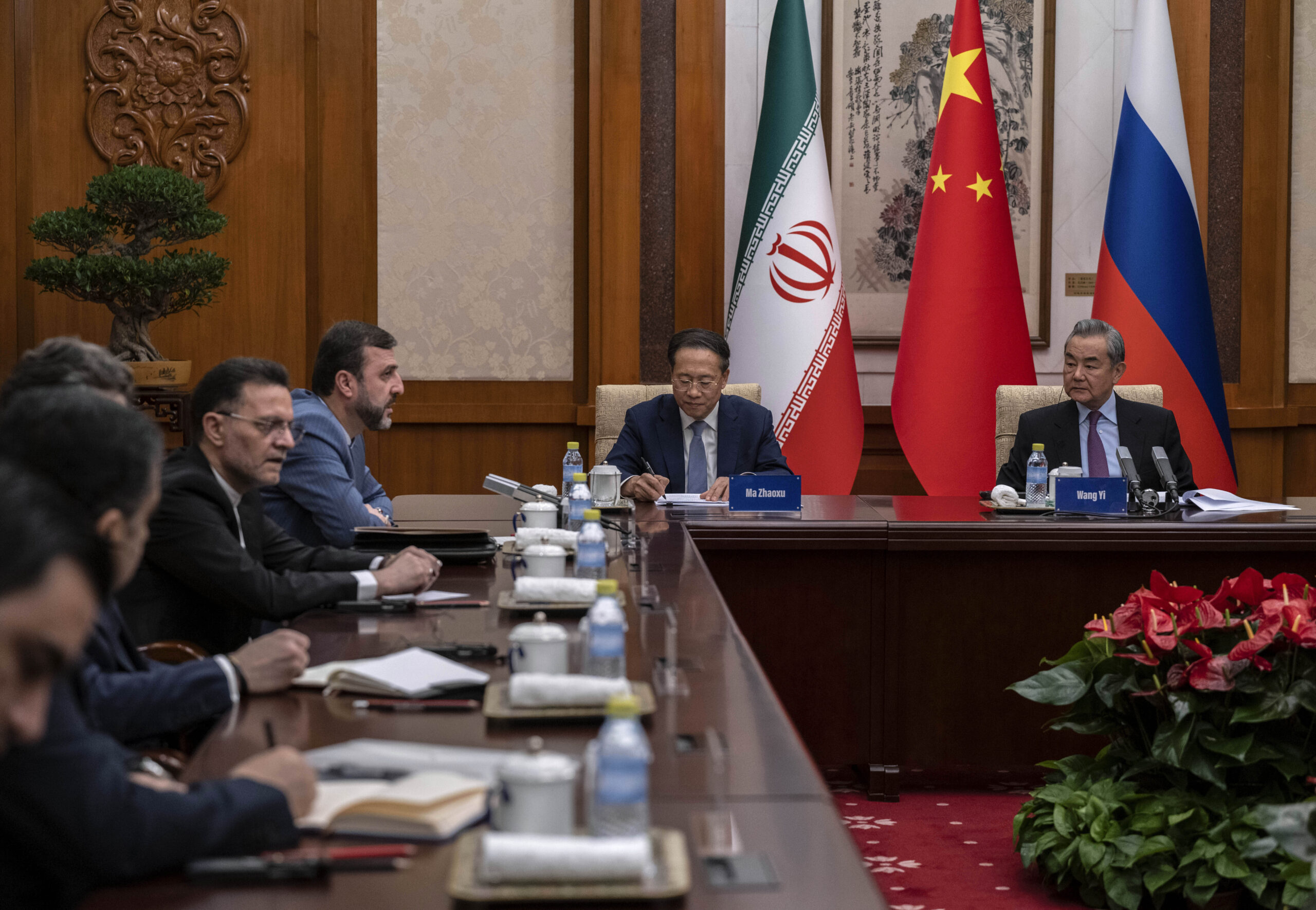

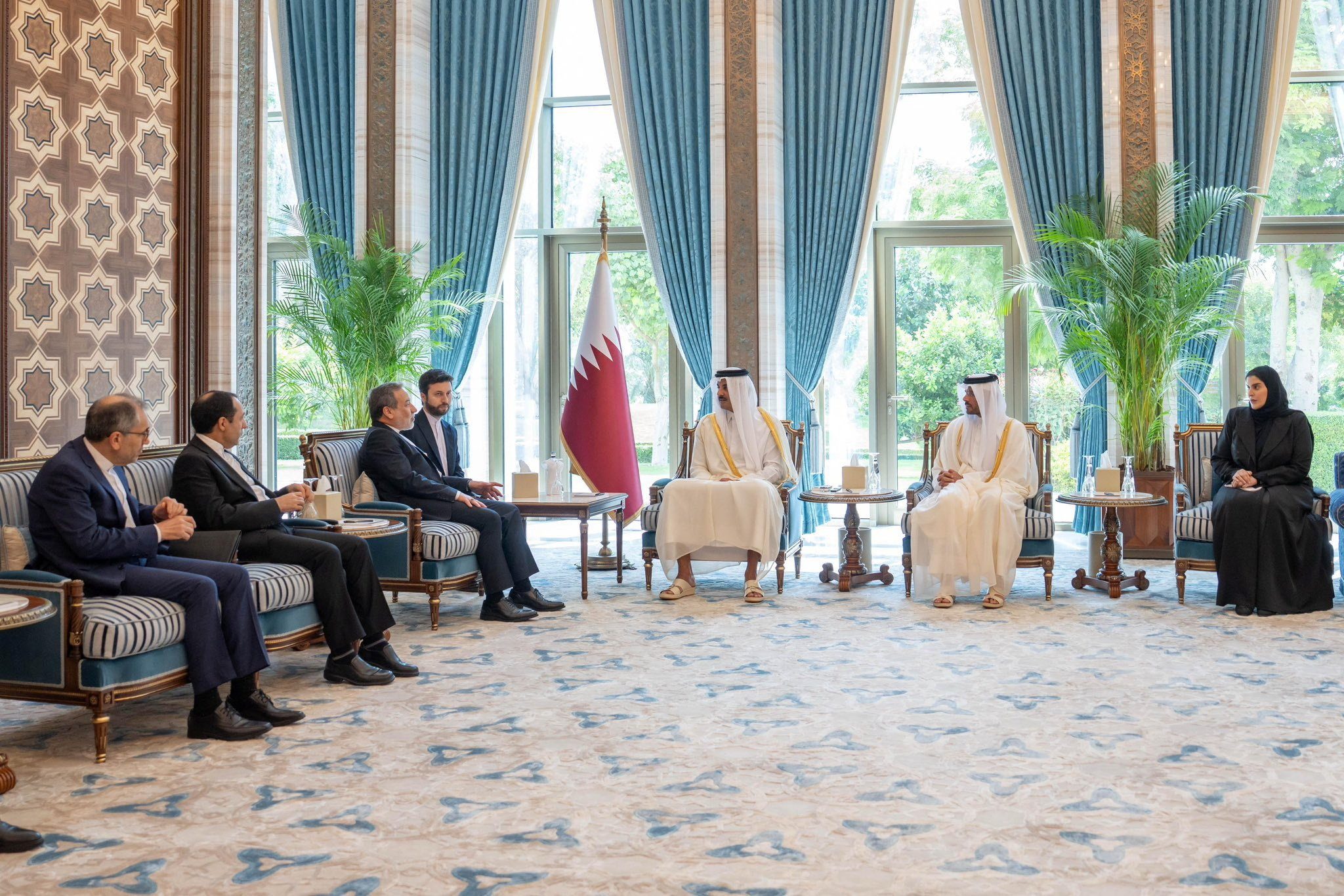

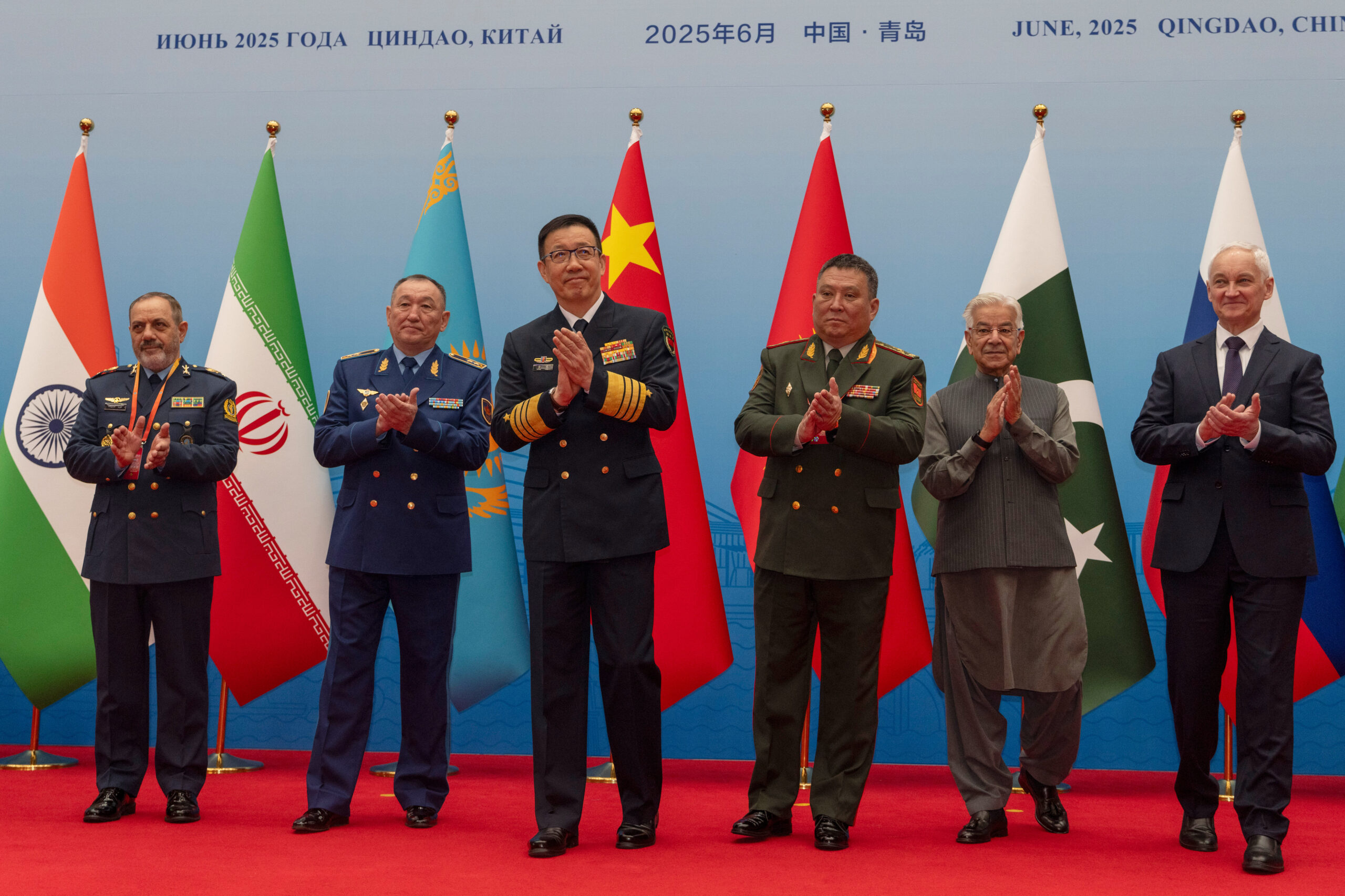

On July 15, Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi attended the Shanghai Cooperation Organization summit in Tianjin and met with Chinese President Xi Jinping – a meeting that underscored the growing strategic weight of Chinese-Iranian relations. Around that time, reports indicated that Iran had acquired Chinese-made surface-to-air missile systems through an oil-for-arms arrangement.

Deepening Chinese-Iranian Defense Ties

Tehran was frustrated by Moscow’s perceived lack of support during the recent conflict with Israel. Determined to rebuild its missile and air defense infrastructure, Iran now regards Beijing as its most reliable partner in this critical area. While China, according to Western and Israeli sources, provided Iran limited logistical and technical support after Israel’s October 2024 strikes targeting Iranian military sites, the current cooperation marks a new phase with deeper Chinese involvement in the reconstruction of Iran’s damaged air defense systems.

Although China denies transferring complete weapons systems, Chinese firms have supported Iran’s missile program by supplying dual-use materials. Notably, Chinese firms have supplied Tehran with shipments of sodium perchlorate – a key precursor in the production of ammonium perchlorate, an essential component in solid rocket fuel.

In April, the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control targeted several China-based entities – Shenzhen Amor Logistics, Dongying Weiaien Chemical, Yanling Chuanxing Chemical Plant General Partnership, China Chlorate Tech, and Yanling Lingfeng Chlorate – for their roles in facilitating the transfer of dual-use materials to Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. These actions were part of a broader effort to disrupt procurement networks supporting Iran’s missile program. Months later, following the June conflict, Israeli Ambassador to the United States Yechiel Leiter described indications of China’s involvement in rebuilding Iran’s missile arsenal as “troubling,” saying that Israel doesn’t “want to see China acting alongside those who threaten our very existence” – a pointed message considering the general stability of Chinese-Israeli relations.

As both the United States and Israel intensify efforts to prevent Tehran from reconstituting its missile capabilities, the deepening defense and technological cooperation between China and Iran presents a serious strategic challenge. This evolving alignment has potential to undermine Western containment strategies and shore up Iran’s deterrent posture.

Strategic Central Asian Corridor

Iran seeks greater strategic autonomy and economic resilience by expanding overland trade routes with China through Central Asia. These corridors reduce Tehran’s reliance on the Strait of Hormuz, mitigating risks from future conflicts or sanctions – concerns amplified by the June conflict with Israel. While the conflict accelerated these efforts, the underlying strategy predates it and reflects a broader “look East” policy aligned with Iran’s participation in China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Tehran sees deeper integration into East-West connectivity frameworks – notably those that bypass Western-dominated maritime lanes – as a means of economic diversification and a geopolitical hedge against isolation. These initiatives aim to institutionalize Iran’s economic ties with China and Central Asia while reinforcing its commitment to a multipolar order.

In May, Tehran hosted a meeting with senior railway officials from China, Turkey, and several Central Asian states to advance discussions on the development of a transcontinental rail network. Later that month, a freight train departing from Xian (the capital of China’s Shaanxi province) arrived at Iran’s Aprin dry port, marking the inauguration of a direct rail link between the two countries. The train, which transported solar panels, traveled through Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan. This new route cuts transit time to about 15 days – half the 30 to 40 days required by sea.

Concurrently, Tehran is seeking to capitalize on China’s expanding trade connectivity with Central Asia, viewing this momentum as an opportunity to more deeply embed itself within emerging trans-Eurasian transit corridors. Notable initiatives such as the Ayagoz-Tacheng railway link and the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway project illustrate Beijing’s growing infrastructure footprint in the region – an evolution Tehran aims to leverage for its own strategic benefit. Iran is also prioritizing its role in the International North-South Transport Corridor, a multimodal transit network designed to connect Russia’s Caspian and Baltic Sea ports to the Gulf and India, with its western branch passing through Azerbaijan and its eastern corridor transiting Afghanistan. From Tehran’s perspective, these diversified overland routes serve multiple strategic purposes: reducing dependency on maritime chokepoints, including the Strait of Hormuz, mitigating the impact of Western sanctions, and limiting the economic fallout of potential military escalations involving the United States or Israel.

Strategic Synergies

China is expanding military cooperation and economic connectivity with Iran, especially via Central Asian trade corridors, to advance its broader geopolitical and geoeconomic goals. Although Beijing is unlikely to intervene militarily in future Iran-Israel conflicts, it has tangible interests in supporting Tehran – such as assisting with missile rebuilding – while stopping short of endorsing any Iranian nuclear ambitions. From China’s perspective, Iran serves as a critical counterweight to U.S. influence in the Middle East. The two countries are bound by a shared interest in promoting a multipolar international order and challenging the foundations of U.S. hegemony.

Moreover, China’s interest in bolstering overland Eurasian connectivity, especially considering the vulnerabilities associated with the Strait of Malacca, through which around 80% of China’s crude oil imports flow, further elevates Iran’s strategic relevance. Security risks in Pakistan and the growing complications of transiting through heavily sanctioned Russia make westward routes through Central Asia, Iran, and Turkey increasingly attractive to Beijing. Iran’s geographic position as a linchpin between East and West gives it enhanced leverage in China’s long-term vision for resilient, diversified trade corridors. As these synergies deepen, geoeconomic cooperation between Beijing and Tehran is likely to grow, and their strategic alignment likely to increase.

The June Iran-Israel conflict catalyzed a more decisive and multidimensional Iranian pivot toward Beijing. Confronted with heightened military threats by the U.S.-Israeli alliance and renewed Western pressure, Tehran is recalibrating its strategic orientation to ensure greater resilience through deepened cooperation with China. This alignment, while not without its limitations, serves mutual interests: Iran gains critical military and economic lifelines amid the “maximum pressure 2.0” campaign of the administration of President Donald J. Trump, while China secures a strategic partner positioned along vital overland trade corridors and capable of undermining U.S. influence in the Middle East. As Tehran embeds itself more deeply in China-centric networks of defense and commerce, the United States and Israel will face challenges stemming from an evolved Eurasian order in which the consequences of deeper Chinese-Iranian cooperation across multiple domains will likely complicate future efforts to contain Iran.

The views represented herein are the author's or speaker's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of AGSI, its staff, or its board of directors.