Gulf Exporters Monitor Impact of Russian Oil Sanctions

A decision by President Trump to bring the hammer down on Rosneft and Lukoil could be just what the doctor ordered for Gulf oil exporters.

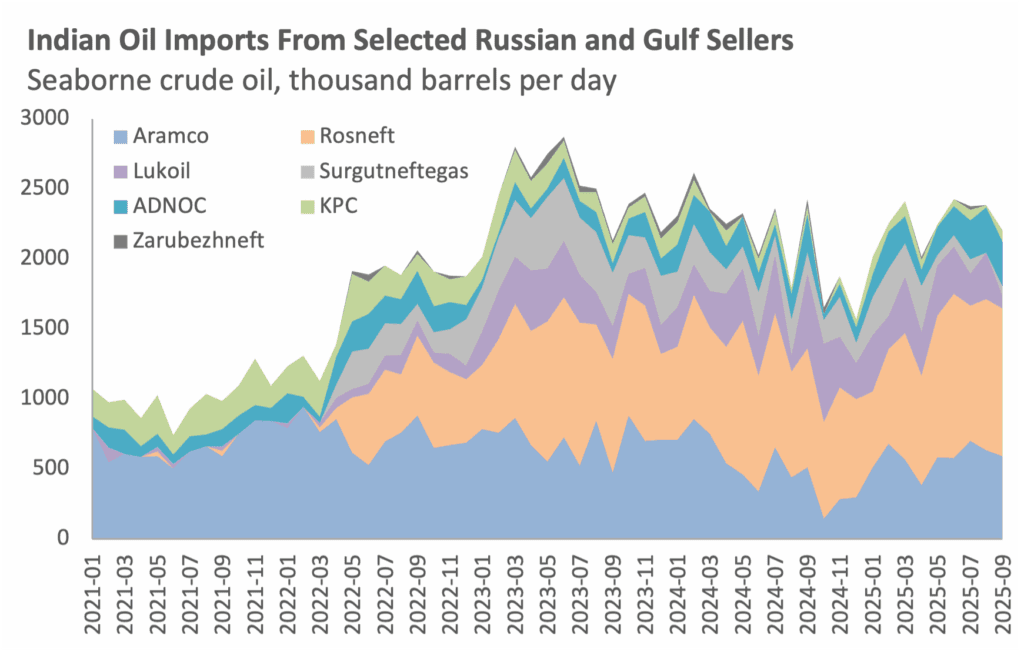

Is Washington finally getting tough on Russian energy sanctions? The oil market is skeptical. Strict enforcement of measures targeting Rosneft and Lukoil – above all, a willingness to impose secondary sanctions on their buyers – could alter crude flows and cut Russian exports. Gulf exporters stand to gain as buyers seek alternatives to Rosneft and Lukoil crude. For now, Gulf exporters are monitoring the market impact as the OPEC+ “Group of Eight” pauses planned supply additions for the first quarter of 2026.

U.S. Treasury Department sanctions on Rosneft and Lukoil target key sources of Russian revenue. Unlike the ineffective oil price caps seeking to lower Russia’s per-barrel revenue, or targeted designations of “dark fleet” tankers and their owners, these sanctions aim directly at two companies that account for almost half of Russian crude oil exports. The Treasury has blocked financial assets held by Rosneft and Lukoil, and their majority-owned subsidiaries, and barred financial transactions with these entities by U.S. individuals, companies, and financial institutions. The Treasury warned that “foreign financial institutions that conduct or facilitate significant transactions” with such entities could be subject to sanctions.

These measures are already having an impact. Lukoil now plans to sell its international assets to trading giant Gunvor, possibly at a hefty discount. And companies have until November 21 to wind down transactions with Rosneft and Lukoil. For most international companies, the threat of secondary sanctions is too big to ignore.

Time will tell whether Washington chooses the path of strict enforcement. Fellow G7 states seem confident that a coordinated effort can dial up pressure on Russian oil exports. Perhaps the administration of President Donald J. Trump is finally determined to force Russian President Vladimir Putin to get serious about negotiations over peace in Ukraine, even if this entails a hit to global oil supply. If not, sanctions will simply redirect volumes in an ever more opaque oil market, with Russia finding work-arounds, such as new trading entities.

Source: Kpler

Sanctions enforcement centers on Asian buyers, and events in the past few months suggest the Trump administration is more likely to lean on India rather than China. Russian oil exports to India have skyrocketed since 2022, reaching more than 2 million barrels per day in some months. In August, the White House imposed a “secondary tariff” of 25% on Indian goods over the country’s ongoing purchases of Russian oil, added to the 25% reciprocal tariff Trump had imposed on the world’s most populous country. India refused to bow to these tariffs, but now the threat of secondary sanctions has added pressure.

Reliance Industries, operator of the world’s largest refinery, has stated it will comply with new sanctions. Reports suggest it may declare force majeure on its 10-year term contract with Rosneft for up to 500,000 b/d and seek alternative supplies. Indian Oil Corporation will not stop importing Russian oil but reinforced that it will not deal directly with sanctioned entities. And HPCL-Mittal Energy, a joint venture between Hindustan Petroleum Corporation Limited and the Mittal Group, will suspend further purchases of Russian crude. Buyers in Turkey and elsewhere in the Mediterranean will share this caution.

Russian oil exports to China could be less affected, although Chinese national oil companies are wary of sanctions exposure. Since the October 22 Treasury sanctions were announced, state refiners appear to be scaling back their purchases. Private Chinese refiners – often labeled “teapots” despite the large size and sophistication of some of their facilities – are better positioned to avoid Western financial institutions and attendant sanctions exposure. Chinese independent refiners have bought volumes in recent years from sanctioned exporters Iran, Venezuela, and Russia. Perhaps after a pause to monitor enforcement, it will be back to business as usual.

If risk-averse buyers seek alternatives to Rosneft and Lukoil volumes, what are the most likely options? As always, crude quality matters. Most Russian seaborne crude exports are either medium sour or light sour. In the past two years, India imported an average of 1.3 mb/d of Urals crude – Russia’s main sour export blend, normally exported via its Black Sea and Baltic Sea ports. Buyers in India, China, Turkey, and elsewhere may seek alternative crude grades from the Gulf, Iraq, West Africa, and Europe. Trump claimed China would import more U.S. energy supplies after the recent U.S.-China trade truce, and other officials have suggested Russia’s buyers should turn to U.S. volumes instead. But there is a mismatch in crude quality. The bulk of U.S. crude exports are light, sweet crude that does not substitute for Urals. Lighter, lower-sulfur Eastern Siberia-Pacific Ocean crude exported by pipeline from Russia to China is less likely to be affected by sanctions.

What does all this mean for Gulf oil exporters? After the array of sanctions, embargoes, and market interventions by the United States and European Union in recent years, a greater share of traded oil has moved into the shadows. Dodgy traders, tanker owners, and suspect shipping practices have greased the wheels of this maritime trade. Individual crude exporters benefit from discontinuities and friction, for example, when refiners suddenly need alternatives. But what matters most for oil market management is the net gain or loss from market volumes.

To date, Western sanctions targeting Russian oil have yet to remove barrels from the market. This is by design. Policymakers in Washington and European capitals have typically been wary of tough measures that could drive up the price of gasoline or diesel for the average consumer. The new sanctions targeting Russian oil giants – and especially the threat of secondary sanctions – could have real teeth. Especially if Washington policymakers believe the market is heading toward the massive oversupply many anticipate for the first quarter of 2026, they will feel more confident about squeezing Russia’s oil exports.

So far, OPEC+ is not overreacting. On November 2, the “Group of Eight” producers that have led voluntary cuts since 2023 agreed to raise their production ceiling by 137,000 b/d in December but paused planned additions for the first quarter of 2026. This suggests that after raising output for months – although at slower rates than headlines and announced production ceilings would suggest – the producers’ club is wary of an oversupplied market. A decision by Trump to bring the hammer down on Rosneft and Lukoil could be just what the doctor ordered for Gulf oil exporters looking to add volumes and recapture market share. But for now, they will wait and watch. As with many other issues in the global economy and geopolitics, much depends on the decisions of the U.S. president.

The views represented herein are the author's or speaker's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of AGSI, its staff, or its board of directors.