The Gulf’s Return to Lebanon?

A new government and the movement to disarm a weakened Hezbollah are increasing Gulf states’ trust in Lebanon, but Gulf-Lebanese rapprochement is not yet right around the corner.

The Gulf states’ frustration with Lebanon boiled over in 2021, when Hezbollah’s and, by extension, Iran’s influence in Lebanese government affairs was near its peak. Led by Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates effectively boycotted Lebanon, emphasizing that in this Mediterranean battleground, they were not going to let Iran and the “axis of resistance” get the better of them. The Gulf states have since set a high bar for a return to normalcy in their relationship with Lebanon, insisting that a pro-Iranian government in Beirut will not be welcomed into the Arab fold and will not receive the financial support desperately needed following the collapse of the Lebanese economy in 2019 and the damage caused by Israeli strikes on Hezbollah in 2024. Although the Lebanese government still has much to do to meet Gulf expectations, a special fondness for Lebanon and the Lebanese has meant that the Gulf states have not fully abandoned Lebanon, and a pathway to restored relations may still exist.

2021: A Bad Year for Gulf-Lebanese Relations

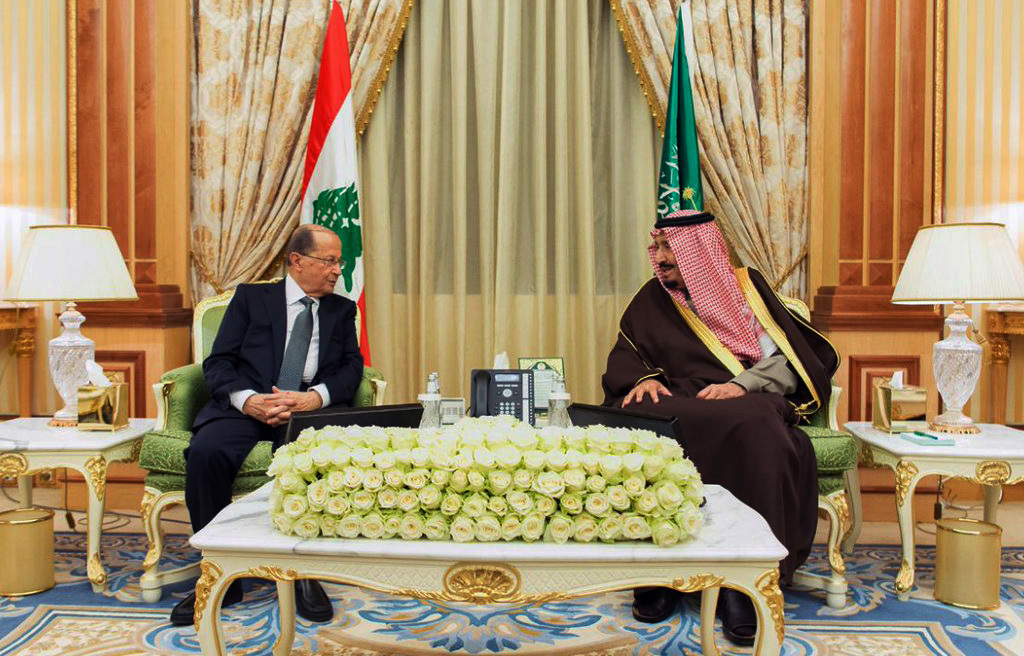

In 2021, Lebanon’s relations with the Gulf states spiraled. Hezbollah maintained its grip on Lebanese politics both through its mafia-like enforcement of order and its long-standing relationship with then-President Michel Aoun and his Christian party, the Free Patriotic Movement. This monopoly cast a large shadow over Lebanese politics and decision making, particularly as it pertained to Lebanon’s relationship with its neighbors.

George Kordahi, who served as Lebanon’s minister of information at the time, made disparaging comments about the Saudi-led intervention in Yemen, calling it “futile and pointless” and said that the Houthis were “defending themselves against an external aggression.” This came six months after then Lebanese Foreign Minister Charbel Wehbe used derogatory terms to describe the Saudis. Many Gulf Cooperation Council countries were convinced that Lebanon was pursuing a pro-Iran foreign policy that was intended to undermine the Gulf’s agenda.

Meanwhile, media accounts reported that Hezbollah was smuggling disassembled weapons into Yemen and conducting training for Yemen’s Houthi fighters. There have even been unconfirmed reports that Hezbollah’s leadership may have influenced Houthi financial and military operation decisions.

Moreover, in April 2021, Saudi authorities discovered a shipment of 5.3 million smuggled Captagon pills in pomegranate crates at the Jeddah airport. The Gulf states viewed Hezbollah’s sway in Lebanon, involvement in Yemen, and effort to corrupt Gulf society through the sale of drugs as a war being waged against them.

Lebanon’s Economic Crisis

In response, Saudi Arabia in October 2021 expelled Lebanon’s ambassador, banned all Lebanese imports, and recalled its ambassador to Lebanon. In solidarity, Bahrain, Kuwait, and the UAE recalled their ambassadors as well. (These Gulf ambassadors have since returned to Beirut). Then, in early 2022, Saad Hariri, Lebanon’s former prime minister and leader of the Sunni community in Lebanon, announced that he would suspend all his political activities in advance of that year’s parliamentary elections. The announcement was linked to tensions between the Saudi royal family and Hariri. Even the Emiratis, who agreed to host Hariri, emphasized to him that he would be allowed to conduct his business affairs in the UAE on the condition that he suspend his political activities.

As Lebanon’s relationship with the Gulf was deteriorating, it suffered the effects of one tragedy after another. In 2019, Lebanon endured a severe economic collapse, as its gross domestic product fell by nearly 40% in real terms, its currency lost 98% of its value, and depositors were not allowed to access their funds held at local banks. In August 2020, during the height of coronavirus pandemic restrictions, an estimated 2,750 tons of unsafely stored ammonium nitrate exploded at Beirut’s port causing the largest nonnuclear blast in modern history, resulting in hundreds of deaths, thousands of injuries, and billions of dollars in damage.

Rather than bringing relief from such tragedies, Iran’s support to Hezbollah has only added to the suffering of the Lebanese people, including the largely pro-Hezbollah Shia population in the south. Hezbollah used its sway to block for more than two years the election of a president that it viewed unfriendly to the group’s agenda, leading to political gridlock and paralysis. It was not until Israel’s attacks in 2024 in southern Lebanon, weakening Hezbollah, that the group realized it could no longer stand in the way of electing the president. And with Joseph Aoun’s election as president in January, the gridlock ended.

What Does Lebanon Need To Do?

In June 2023, the International Monetary Fund issued a report with economic reform recommendations to stabilize the Lebanese economy. The reforms included enhanced governance transparency, a strengthened anticorruption framework, improved performance among state owned enterprises, debt restructuring, a unified exchange rate, and protection for small depositors. It is generally accepted within Lebanon and among international observers that the country’s political elite are deliberately blocking much-needed reforms to protect their financial interests.

Between 1963 and 2022, Gulf states gave Lebanon an estimated $9 billion in grants, excluding loans and investments. But they have stressed that that era is over. Gulf capitals have linked any new financial packages to reforms, such as combatting corruption and restoring confidence in the banking system as proposed by the IMF, and, crucially, disarming Hezbollah. Saudi commentator Ali Shihabi said that Saudi Arabia “does not want to invest in a black hole.”

Like other Gulf states, Saudi Arabia generally frames its position on Hezbollah’s disarmament in terms of support for state control of weapons and in the context of adherence to relevant United Nations Security Council resolutions (which include provisions on disarmament). How a relatively weak Lebanese central government, with armed forces outgunned for decades by Hezbollah, would accomplish such disarmament without prompting significant internal instability remains unclear. However, as the Lebanese government and the international community continue to make progress on the question of Hezbollah’s weapons, it is widely expected that the mafia state created by the militia will no longer be able to survive, and the much needed and long-awaited economic reforms called for by the Gulf states and others will finally be enacted.

In August, U.S. Special Envoy for Syria – and U.S. Ambassador to Turkey – Thomas Barrack announced a plan to disarm Hezbollah by the end of 2025. It outlines an economic strategy for Lebanon that combines regional investment with security reforms. This plan also includes Saudi Arabia and Qatar investing in an economic zone in southern Lebanon to create job opportunities for former Hezbollah members who agree to lay down their weapons. Media accounts indicate that the plan for disarming Hezbollah will rely on persistent Israeli military pressure on the group, which could prolong the depopulation of some border villages and lead to a more militarized southern Lebanon.

Prospects for Gulf-Lebanon Ties

Given the key to any Gulf-Lebanon rapprochement is Hezbollah surrendering its weapons, the path to get there is going to be filled with landmines both figurative and literal. This does not mean that steps can’t be taken to move toward this goal. The first big hurdle was the election of Aoun and the appointment of Prime Minister Nawaf Salam. Lebanon now has a leadership that seems ready to bring the country back into the Arab and Western fold.

In March, Aoun was the first Lebanese head of state in eight years to visit Saudi Arabia, where he met Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. During the visit, the two leaders discussed taking steps to resume Lebanese exports to Saudi Arabia and have Saudi citizens once again travel to Lebanon, according to the Office of the Presidency. In the months that followed, Aoun also visited Kuwait, Qatar, and the UAE to present Lebanon as “open for business.” Saudi Arabia has responded positively and, in November, announced plans to boost commercial ties to Lebanon after reports that “the Lebanese government and security forces demonstrated efficacy in curbing drug exports over recent months,” according to a senior Saudi official.

Accounting for more than 19% of GDP prior to the economic collapse in 2019, tourism has emerged as the fastest route toward restoring ties to Gulf countries and reviving the economy. “Tourism is a big catalyst, and so it’s very important that the bans get lifted,” said Laura Khazen Lahoud, Lebanon’s tourism minister. Shortly after Aoun’s visit, the UAE officially lifted its travel ban on UAE nationals visiting Lebanon, according to the UAE Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Bahrain, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia are considering similar moves. Qatar never imposed a travel ban, so Qatari nationals have continued to travel to Lebanon.

Emirati and Gulf interests in Lebanon are likely to include investments in the energy sector and development of the gas fields in the eastern Mediterranean. The UAE may also be willing to contribute by providing equipment and training to universities and hospitals and by rehabilitating key infrastructure, particularly the Beirut port and the country’s road and bridge networks.

Remittances in Lebanon in 2025 are expected to reach $7.31 billion, with an annual growth rate of 4.5% over the next several years. Before the rupture with the Gulf, the majority of Lebanese expatriates in the Gulf were in Saudi Arabia with more than 300,000, the UAE was close behind with nearly 200,000, and Kuwait had around 42,000. From 2020-22 alone, more than 80,000 Lebanese moved to the Gulf in search of jobs. Remittances from the Gulf remain a critical component of the Lebanese economy.

Approaching the end of the year, Saudi Arabia has already made another strong gesture of support to the Lebanese government. Along with the United States and France, Saudi Arabia announced on December 18 that it will host an international conference early in 2026 in support of the Lebanese army. Aoun expressed his heartfelt gratitude and emphasized his commitment to ensuring that the money will be used in a transparent and responsible manner to help Lebanon resume its rightful place as a member of the Arab nations.

The views represented herein are the author's or speaker's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of AGSI, its staff, or its board of directors.