The Saudi National Transformation Program: What’s in It for Women?

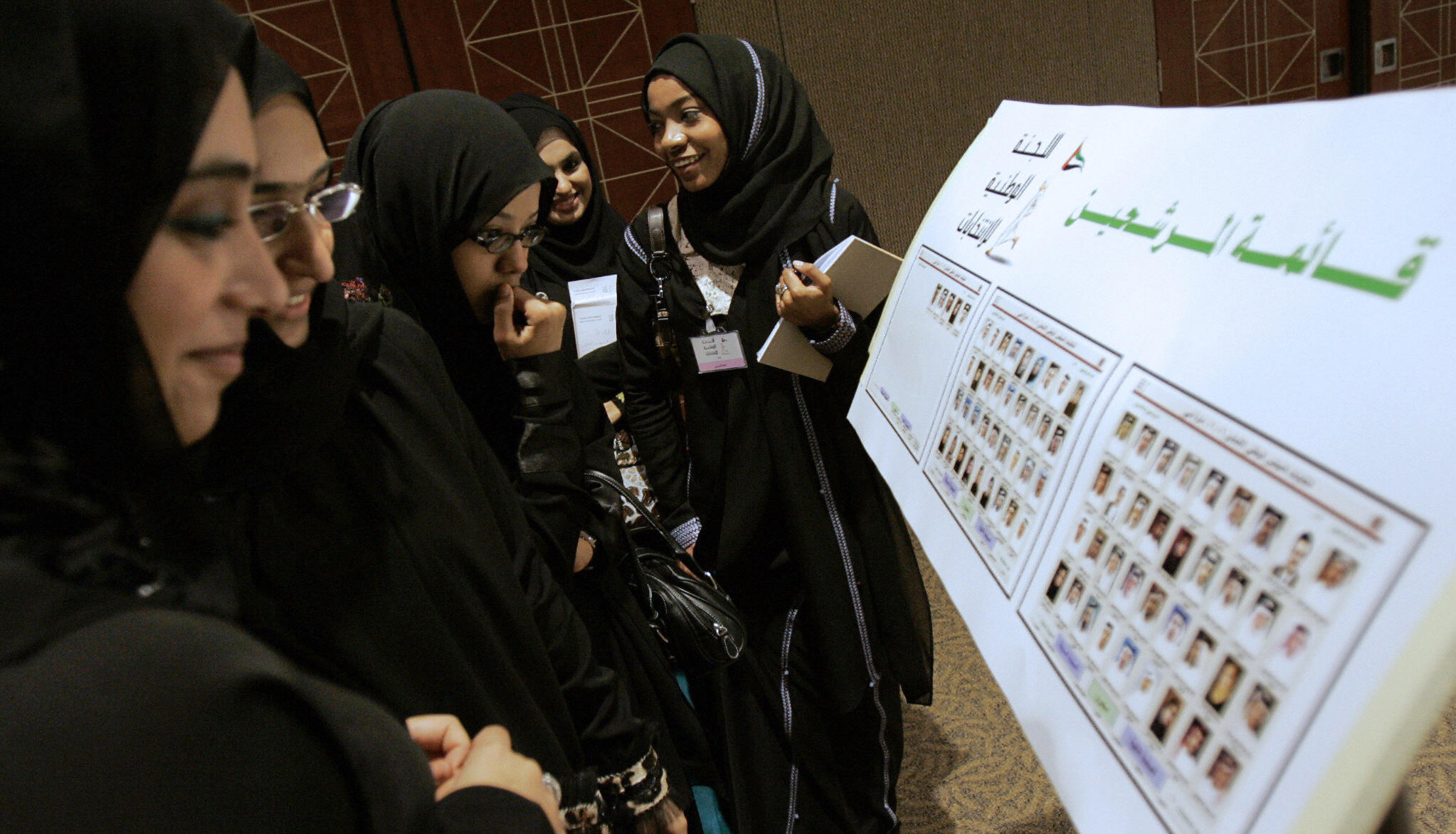

In a national workforce largely composed of men and foreign workers, can economic reform ensure women's participation?

In December 2015, the Council of Economic and Development Affairs in Saudi Arabia announced the National Transformation Program (2020). The core of the plan is economic reform with a focus on increased employment, privatization, and monitoring of ministerial performances. With the reduction of the public sector, there will be a shift in employing Saudi nationals in the private sector, currently dominated by low-skilled and low-paid foreign workers. There is a large downward gap of about 70 percent between the wages of the public sector, where most Saudi nationals are currently employed, and private sector, making the latter a rather unattractive option. In a national workforce largely composed of men and foreign workers, can economic reform ensure women’s participation? And would legal restrictions on women’s autonomy be considered in the reform plans?

The National Transformation Program

In Saudi Arabia, women university graduates outnumber men. However, their representation remains minimal in professional jobs or key positions across various sectors. Currently, women’s participation in the workforce sits at merely 21 percent and represents only 18 percent of the female working-age population. Moreover, the national transformation program targeted certain sectors for privatization such as mining and religious tourism, where women’s jobs are generally limited. In his interview with The Economist, Prince Mohammed bin Salman, Saudi Arabia’s deputy crown prince, acknowledged that the decades-long investment in women’s education is unmatched by their economic participation stating, “A large proportion of my productive factors are unutilized,” referring to Saudi women. He added, “I have a population growth reaching very scary figures.” However, Salman attributed the significant women’s unemployment rates to social norms and attitudes rather than to governmental restrictions noting, “A large percentage of Saudi women are used to staying at home. They are not used to being working women.” When asked about the obvious restrictions on women’s participation such as the driving ban, he declined to intervene in this issue, viewing it as a societal decision.

In fact, challenges to women’s economic participation and opportunities are more embedded in political restrictions than in cultural ones. In recent years, the government policy of feminizing retail business (catering to women clients) resulted in a 12 percent increase in women’s jobs with little, if any, societal resistance. However, this gender-specific hiring policy may not be sufficient in male-dominated professions such as law and engineering, where women graduates are increasing in number while gender segregation policy is still enforced. In a survey of 3,000 Saudi nationals, barriers to seeking jobs for women were identified as transportation by 46 percent of respondents and daycare facilities by 40 percent. The survey also identified several determinants for women seeking jobs including pay level (75 percent), hours (66 percent), distance from home (50 percent), and availability of transportation by employers (34 percent). Gender segregation or societal acceptance was rarely a factor.

The Saudi government has planned taxes and subsidies, some of which have already come into effect to support the public budget. It is considering introducing a valued-added tax in line with a three year Gulf Cooperation Council-wide VAT recommendation. The government has planned a 2.5 percent land tax on large stretches of undeveloped and privately owned urban lands. The tax came in response to a shortage of lands needed to implement the state-assisted housing program Eskan. Only families can apply to the subsidized state housing, as women traditionally do not live on their own. However, exceptions were made for widowed or divorced women. An approximate increase of 50 to 67 percent in gas prices, 40 percent in electricity expenses, and 200 percent in municipal water costs is expected to cause a 58 to 113 percent increase in household expenditures on gas and utilities. Currently, there are an average 1.5 workers per household and unless women too also employed to compensate for the expected reduced income, many households will be impacted. To meet the expected reduction in household income by 2030, an investigative economic report by McKinsey Global Institution (MGI) recommended an increase of female labor participation to 32 percent. Reforms of regulations, foreign investment, and business processes must be implemented along with efficient fiscal management to reach such a drastic and short-term increase in women’s participation. Assuming the situation persists, in which female labor rates are very low and access to resources is limited, the MGI target seems farfetched.

When the Hafiz program to support unemployed youth seeking jobs was announced in 2011, 85 percent of its eligible beneficiaries were young women. In fact, one of the primary criticisms of the national transformation program is the impact of withdrawing public support from vulnerable groups, mainly women, in the absence of alternative options such as work opportunities. The 2015 release of the civil society organizations law after years in review seemed to be timed to enlist civil society’s help in meeting the expected deficiency in welfare support. When asked by The Economist, about the government-enforced guardianship system, which requires all women regardless of age to obtain a male guardian’s permission to travel, marry, work, or pursue many other options, Salman again put the onus on social or religious restrictions that his government cannot change, denying that women in Saudi Arabia require their guardian’s permission unless they are under a certain age. The official restrictions on women’s travel for work or education, getting identification documents, or assuring protection from sexual harassment have placed Saudi Arabia at the bottom of countries measured for women’s labor participation.

The MGI report recommends full participation of stakeholders in policymaking, arguing that efficient economic reform requires a societal collaboration by accommodating public needs. Women facing restricted autonomy and limitations in seeking or maintaining jobs, finding resources, and obtaining legal redress may not be fully equipped to engage in a competitive labor market. Unchecked discriminatory policies and norms remain a major obstacle to full economic participation, and hence the ability to earn income and support the state’s economy. A holistic approach to economic reform in which women are empowered politically and economically can reduce the drastic gap between men and women as measured by the global gender gap report. Acknowledging gender-based barriers in any transformational program is key to a sustainable economy, not only to include more women in the labor force but also to keep them there.

The views represented herein are the author's or speaker's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of AGSI, its staff, or its board of directors.

May 15, 2017

Saudi Arabia’s Post-Oil Future

The euphoria that accompanied the launch of “Saudi Vision 2030” has begun to dim in the face of fundamental challenges. Deputy Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman Bin Abdelaziz Al-Saud’s ambitious plan to steer the country’s economy away from oil dependency and through an era of austerity seemed to offer a much-needed roadmap for overdue reforms....

5 min read