The Rise of Gulf Animation

Animation in the Middle East is a quickly growing industry, and Gulf countries are playing a leading role in creating, funding, and distributing animated stories from the region.

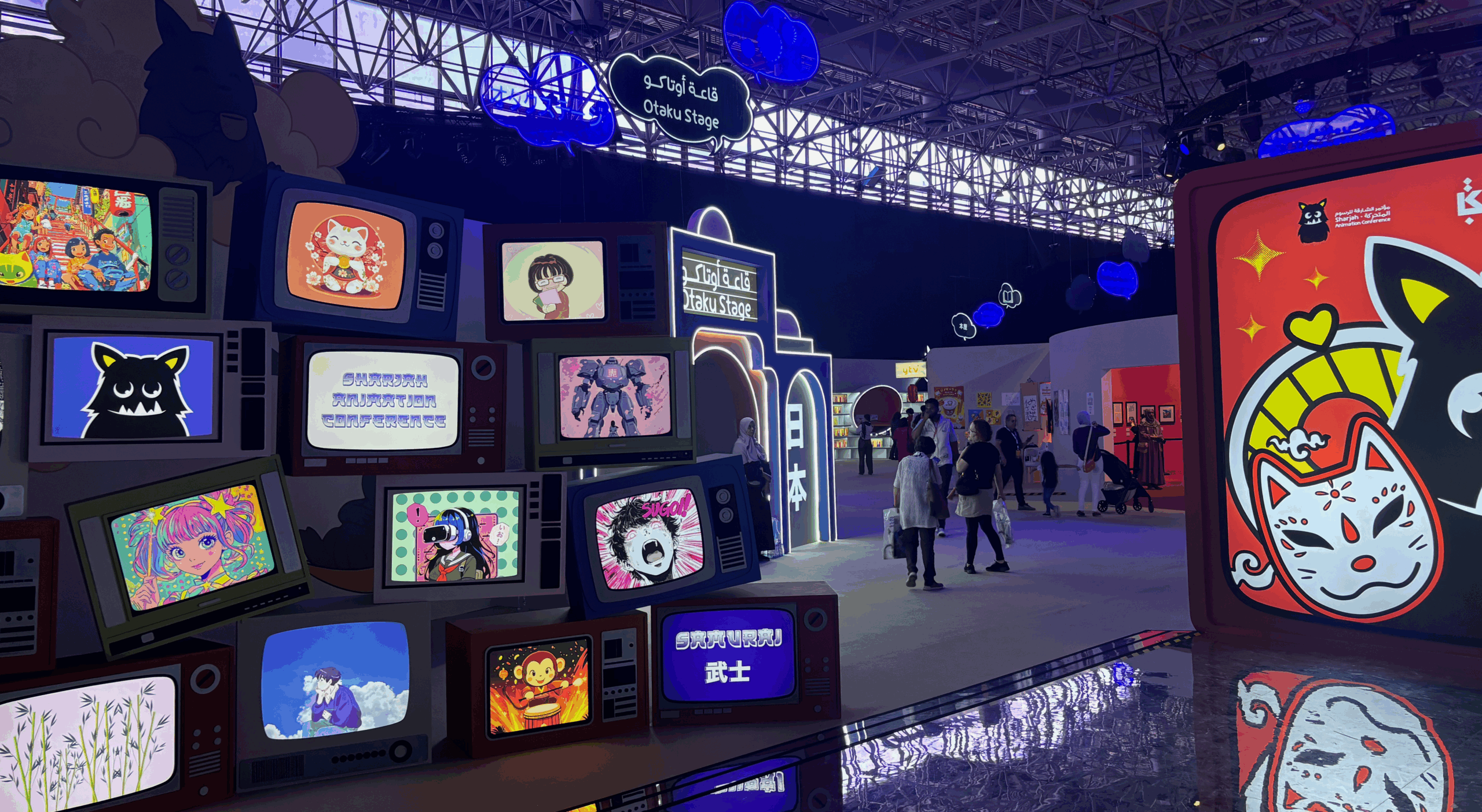

On May 5, Abu Dhabi made headlines as the site for the next Disneyland theme park – the first in over a decade. Just the day before, the Sharjah Animation Conference, which welcomed animation experts and enthusiasts from around the world to the United Arab Emirates, concluded four days of panels, workshops, and film screenings. The agenda featured animators, directors, producers, and media executives from across the Arab world and globally, with Saudi Arabia’s MBC, Dubai-based Spacetoon, the United States’ Cartoon Network, Japan’s Studio Ghibli, and former Disney animators in attendance. The conference and Disney’s announcement highlight the growing impact and reach of the animation industry in the Gulf and wider Arab region.

Animation in the Arab World

While the Gulf has played a key role in the recent growth of Arab animation, today’s industry stands on the shoulders of a rich history of Arab animation dating back to the 1930s, when cinemas in Egypt began to screen U.S. productions. Hits such as “Mickey Mouse” and “Felix the Cat” inspired local artists, including the Frenkel brothers, three sons of Russian Jewish immigrants who produced the first short celluloid films. They produced nine episodes of the series “Mish Mish Effendi” between 1937 and 1950 before they were forced to leave Egypt. Yet, from the 1930s to 1990s, the small but growing animation industry, producing primarily commercials, was dominated by Egyptian animators, joined by Algerian and Tunisian animators in the 1960s. By the late 1990s, Arab animation production began to expand with the spread of Arab satellite channels and the introduction of modern animation technologies. However, there were no specialized children’s channels. Instead, major channels would broadcast children’s programming at a specific time each day, mostly Japanese anime.

That changed in 1997, when the Disney Channel launched in Arabic and English across the region. In 1999, Bahrain Radio and Television Corporation signed an agreement to broadcast a children’s cartoon channel. Then, in 2001, Spacetoon launched as the first Arab, free-to-air animation and anime channel – revolutionary as the first to broadcast Arabic-dubbed anime 24 hours a day. Since then, Spacetoon has transformed into an entertainment powerhouse for families across the Middle East and North Africa, with headquarters in Dubai and local offices in Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Egypt.

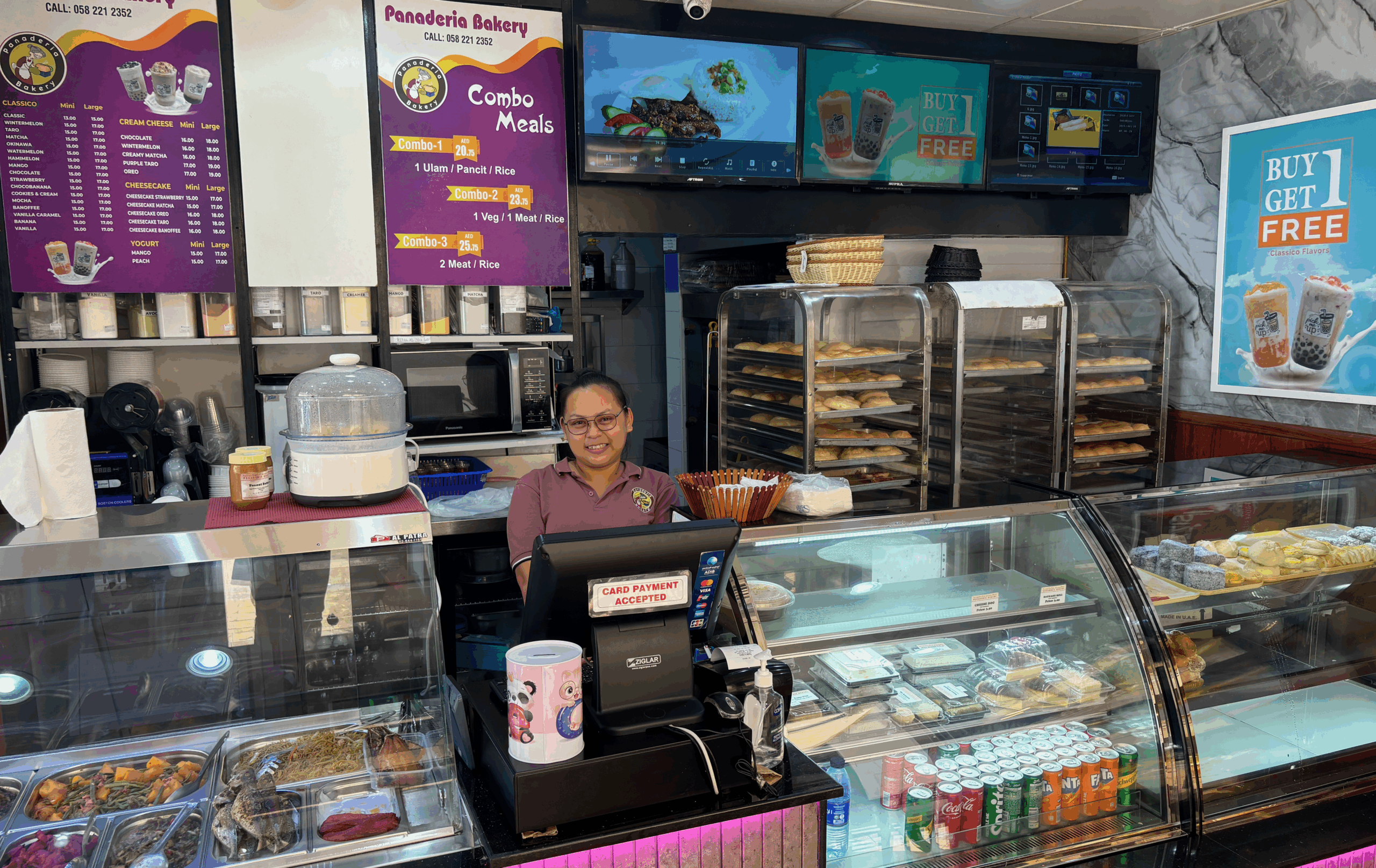

Panelists during “Broadcasting Animation: A Global Perspective on Content, Collaboration” at the Sharjah Animation Conference, May 2025. (Credit: Lauren McMillen)

Sharing Gulf Stories

Over the past decade, the UAE and Saudi Arabia have played key roles in the Arab animation industry through investments in productions at animation studios in the Gulf and wider region, representing stories and characters that reflect Arab histories and culture. In 2006, the Dubai studio Lammtara Pictures premiered one of the first major 3D animated series in the region, “Freej,” with funding from the Dubai government. “Freej” (neighborhood in the Emirati Arabic dialect) depicts the lives of four elderly women navigating life in modern Dubai. With the help of government promotion, “Freej” became a national icon and part of local popular and commercial culture, through contracts with state companies, such as FlyDubai, and the opening of a theme park. In 2018, “Freej” became the first solely Arab-produced animated TV show to be dubbed in Japanese.

In an essay for The Gazelle, Dubai native Roudha Almarzouqi described the show as merging “aspects of old and new Dubai while demonstrating the UAE’s culture and values.” She noted that it was “one of the very few, if any, cartoon shows based in the UAE that showcases Emirati daily life and heritage.” For example, the four women who are the main characters wear traditional Emirati dress, cook traditional Emirati dishes, and converse in the Emirati dialect. She continued, “’Freej’ is much more than a show to me; it is a piece of my childhood and is filled with memories of my younger self.”

Another UAE-based series is “Ali and the Secret Gate,” created by Dubai-based North Wind Studio. Kristina Kleymenova, one of the founders of the studio, said a key challenge in the animation field is successfully pitching original, local content to broadcasters, who “tend to play it safe by airing what’s already been successful internationally.” In contrast, Kleymenova wants to bring the unique experience of children living in Dubai, a city in which almost 90% of its population are expatriates, to the screen by representing the numerous cultures and languages that children navigate each day.

In 2013 on YouTube, Abu Dhabi-based Bidaya Media launched what would become one of the most popular animated series in the region, “Mansour.” Written for 6-9 year olds, the series highlights the importance of family, cultural diversity, and creativity. Bidaya’s creative director, Adam Khwaja, said in 2023 that the YouTube channel logged 392 million hours of watch time and 2.5 billion views. “Mansour” was the first original Arabic cartoon series to reach that many viewers, the majority of whom came from outside the UAE. The popularity of “Mansour” prompted the studio to launch a reboot, “The Adventures of Mansour: The Age of A.I.,” which will feature an animation “upgrade” and a mixture of Arabic dialects from Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Yemen, Egypt, and Sudan. By incorporating themes including artificial intelligence and climate change, Bidaya aims to reflect “a more modern Arab society, rather than an outdated stereotype.”

Alongside the UAE, Saudi animators and broadcasters are playing a growing role in bringing Arab animation to audiences in the region. In 2011, Saudi-based broadcaster MBC aired “Al-Masageel,” the first animated sitcom representing Bedouin history and culture. The series was produced by the Amman-based Sketch in Motion Animation Studio and ran for three seasons. In 2020, after signing a five-year exclusive partnership with Saudi animation studio Myrkott to bring viewers Saudi-focused content, Netflix debuted “Masameer County.” On July 7, 2021, “Masameer County” set a record for consecutive days in the number one position on Netflix’s top 10 chart for TV shows in Saudi Arabia. “What Masameer County exemplifies is the freedom of the Saudi artistic imagination, which is shocking, stunning, hilarious, and wild,” wrote Sean Foley, author of “Changing Saudi Arabia: Art, Culture, and Society in the Kingdom.” He highlighted that the series provides Saudi society with a framework for discussing contentious issues by being able to present them as apolitical. While episodes have dealt with taboo topics, such as homosexuality, “national leaders are not discussed,” he noted, “and nobody is really blamed for the problems facing society.”

While UAE- and Saudi Arabia-based production studios fund and plan many new animated series in the region, animation studios in Egypt or Jordan are often contracted to animate them. Yusuf Khaled, an Egyptian filmmaker, animator, and visual artist and creative technologist at ZANAD Studio in Cairo, discussed the impact of Gulf funding on the wider animation field. “The Gulf region is sort of dominating the production scene, where the contracts will outsource people from Egypt and actually transfer them to their countries to start studios,” he said. “I know many people who went to Saudi Arabia to start studios there. It’s kind of cheap labor compared to Europeans or Westerners, and you get quality work.”

Arafa Nasser, founder and CEO of Oman’s only animation studio, Coco Productions, also underscored the significance of Gulf funding for creative work. “In the UAE, people are much freer with their financial investments when it comes to creativity,” she said. “On the other hand, when it comes to Oman, you have to fight for opportunities and really work hard to make people feel like it’s worth it, and a lot of it is commercial. It pays the bills, but sometimes it’s like – you’re a creative! You have all of this energy and imagination and places you want to go with it, but you’re confined.”

Nasser is building the Gulf country’s animation industry from the ground up. After studying and working in architecture for eight years, Nasser completed a second bachelor’s in animation at SAE University College Dubai, which offers the UAE’s only bachelor of animation program. She began working at BetterJune Entertainment, where she played a key role in the production of “Ajwan,” the first Arabic sci-fi animation. “The caliber of work I was doing with ‘Ajwan’ and BetterJune – they were trying to put themselves at a place where they could compete with international standards,” she said.

However, after deciding to return to Oman, Nasser struggled to find a production company with an animation department at all. “I was like, well, there is no animation industry here, whatsoever, in Oman,” she said. “In January 2023, I decided I was just going to do it – start my own studio.”

Since then, Nasser’s Coco Productions has produced a wide variety of animations, primarily for use in live action shows and films as well as commercials. Yet, Nasser’s passion and heart lies in more creative productions. “We did a project this year for the Oman Pavilion in the Japan Expo in collaboration with Oman-based jewelry company Rahina. It’s a beautiful project, a traditional Omani board game,” she said. “Omani jewelry designer and artist Fatma al-Najjar created a large version of the game for the pavilion, so another Omani animator and I created an animated video in Japanese and English to explain how to play. We took influences from cute Japanese animation. That was really cool – it was a home-grown Omani thing, it went abroad. I was really, really proud of that one.” While the studio is only two years old, Nasser’s work has made a name for itself not only in Oman but in the wider region. “A lot of the work I’ve had at Coco has been industry word of mouth,” she said. “I’m really proud of that.”

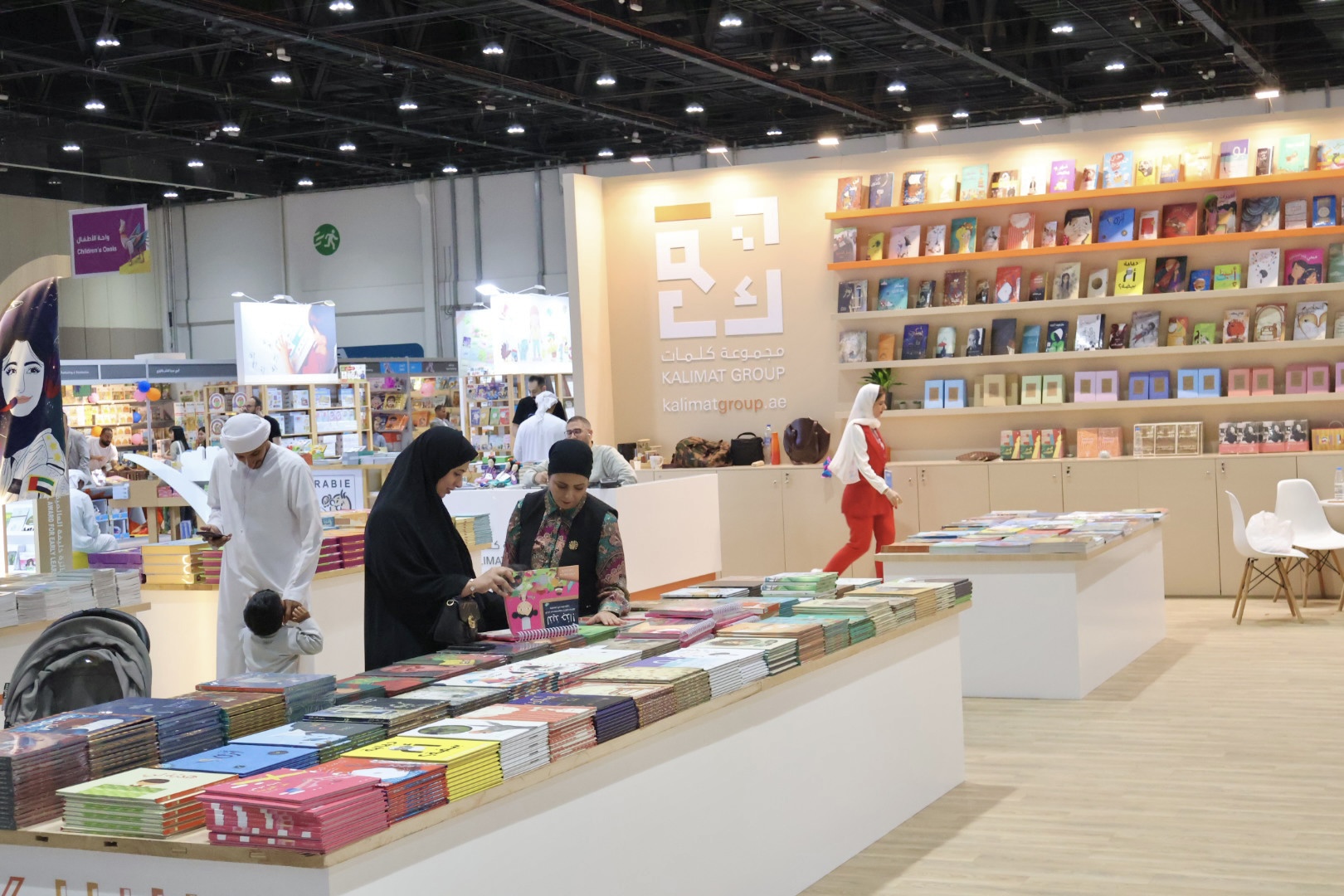

The “Superheroes” exhibition at the Sharjah Animation Conference, May 2025. (Credit: Lauren McMillen)

Fostering Arab Animation

Perhaps one of Sharjah Animation Conference’s most illustrious guests was Disney animation legend Anthony Bancroft. Bancroft co-directed “Mulan” and created beloved characters including Pumba from “The Lion King” and Kronk from the “Emperor’s New Groove.” He spoke about the crucial nature of governmental support in scaling the animation industry. “Tax credits are really the main answer. Thriving industries like Montreal or Toronto – the reason they have industries that are budding up is because their countries have tax credits that would help the producers of the project to do production for less money. Most studios, like Nickelodeon, Disney, or DreamWorks, will do the pre-production, character design, and visual development and then send it all overseas,” he explained. “So, instead of paying $50 million, if they outsource to do the animation in Canada, it’s like they paid $30 million. They’ve saved $20 million.” Bancroft said, “If the UAE wants to work with studios in California, like Disney, DreamWorks, and Sony, they just have to go to them and say: We can give you 30% tax credit if you do 90% of it here.”

Bancroft also highlighted the importance of accessible animation education. “You have to have schools,” he said. “My brother and I started an animation department at a local school. So, not only do we do an animation expo, but we run the animation department, and we’re growing the industry that way. Pretty soon, we can show our talent by doing a short. That becomes a calling card. Then, we show Disney, we show DreamWorks. Hey, this is what we can do.”

Mohamad Hamad, a comic designer and lecturer in animation at the German University in Cairo, also stressed the importance of university animation courses. “It’s a very growing medium, especially in the Middle East. But the main challenge is trying to convince students to actually fall in love with animation,” he said. “It scares them, because it’s a lot of work and time. But animation is all about passion. You have to love it to know how to make it.”

Both Bancroft and Hamad emphasized that, above all, creating spaces for networking and collaboration in the industry is the most important element in fostering homegrown animation. Bancroft said the Sharjah Animation Conference was “a great way to do this.” He continued, “This is where people make connections. They’re also learning and growing, but getting people together in a hub, creating those relationships and connections, is the big first step.” Hamad stressed, “The beauty about animation and design itself is bringing people together to do interesting work. That’s why I love it, it’s so beautiful.”

The Growing Phase

At the 40th anniversary of Spacetoon in 2024, Jun Imanishi, the consul general of Japan in Dubai, told Arab News Japan that “Animation isn’t just about entertainment; it is a soft power that can influence values, lifestyles and inspire the minds of the youth.” Beyond the economic benefits of supporting Arab animators, directors, and producers, fostering the Arab animation industry is crucial for producing stories that portray the diverse perspectives, stories, and experiences of the world’s 450 million Arabic speakers.

Beyond Arab animation reaching global audiences, the growth of the industry allows animators to remain in the region, continuing to invest in it. Farah, born and raised in Sharjah, is currently pursuing an undergraduate animation degree at North Carolina State University. She said that her goal is to work in the animation industry in the UAE. “It’s pretty clear that the animation industry in the Middle East is still in its growing phase. That said, ideally in the end I would like to end up in the Middle East, doing my own thing,” she said. “I want to tell stories that represent my own culture and the values and themes of our own culture, because it is not as represented in the media. Whether it ends up being a worldwide thing or not is out of my control. But I want to do it because I want to know that it’s here.”

The views represented herein are the author's or speaker's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of AGSI, its staff, or its board of directors.