Ammar Alsabban: Superman With a Saudi Accent

With passions as diverse as puppetry, podcasting, and superheroes, Ammar Alsabban is redefining the creative limits of Saudi identity.

Throughout his childhood, Ammar Alsabban’s parents worried about him and his future. No matter how hard the two university professors encouraged their son to focus on his studies and future career, he regularly watched television, played video games, doodled, or daydreamed – none of which, in his family’s eyes, had any career potential. Decades later, the behavior that once troubled his parents had, ironically, laid the groundwork for him to become a successful creative who provides edutainment (entertainment with an educational focus) to people of all ages in Saudi Arabia and across the world. His career since 2013 has included jobs as diverse as puppeteering for an Arabic version of “Sesame Street” and producing podcasts and superhero stories. These creative activities align with the blueprint for today’s Saudi Arabia: the Vision 2030 initiative launched in 2016 by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman that expands the Saudi economy from a dependence on energy exports to include the arts as a pillar of development and a tool for renewing Saudi identity.

Ammar told AGSI that as a boy he dreamed of participating in the television shows and cartoons that he watched – often memorizing and recreating the scenes he saw from “Duck Tales,” Japanese anime (dubbed in Arabic), “The Muppets,” “Sesame Street,” and other shows. He imagined himself as a cartoon character or one of the puppeteers featured on “The Muppets.” He said he spent hours thinking about “the mechanism of how they’d get the mouth moving, hand gestures and a million questions.” He idolized Mel Blanc, the American actor who was the voice of Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, and other Looney Tunes characters. Ammar’s passions and interests, however, did not translate well into his schoolwork because, as he explained to AGSI, he “loved learning but was uncomfortable within the confines of a traditional classroom.” His unease with conventional learning was so great, he added, that he convinced his parents to let him study “for a two-year diploma to be a mechanic and skip college” since he “liked to work with his hands.” His uncle suggested that he check out architecture school – a profession Ammar reasoned would allow him to express his creativity in a manner that would be accepted by his parents and society.

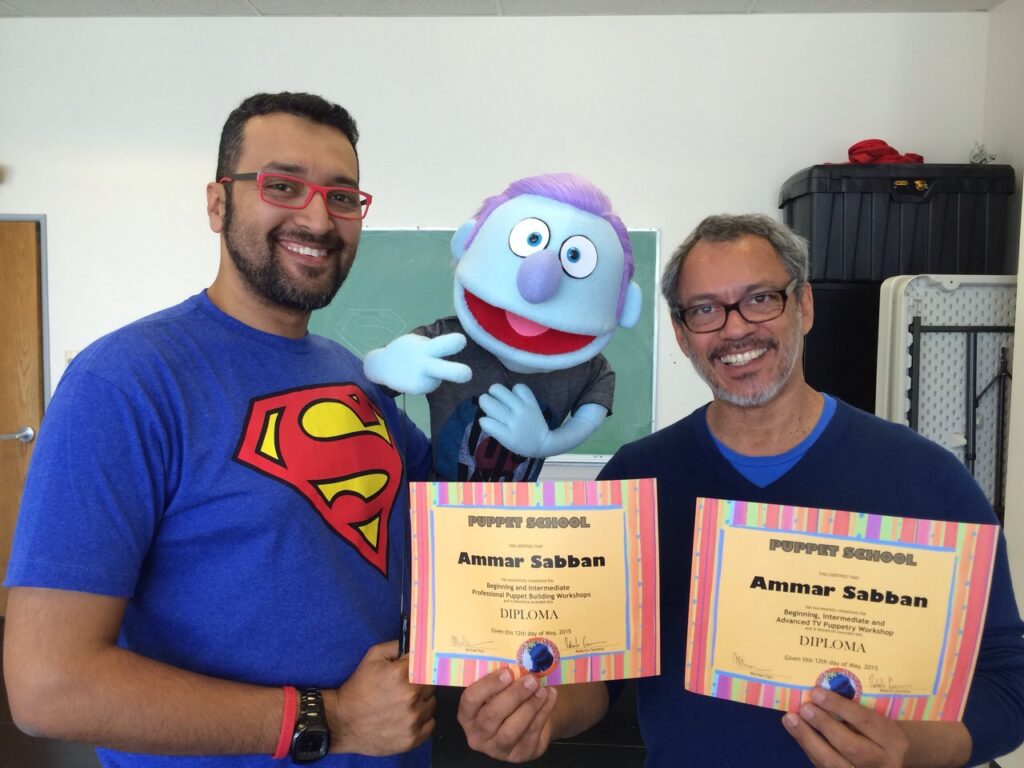

Those hopes went unfulfilled, and, in 2013, after 11 years working as an architect, Ammar quit his day job and focused on his childhood dream of working in entertainment. He watched every video tutorial he could find on puppeteering, especially those featuring Jim Henson, the co-founder of “The Muppets” and a central figure in “Sesame Street.” He traveled to the United States, where he had attended graduate school, to get professional training as a puppeteer. In San Francisco, in just 10 days he completed a two-month course on puppet building and designing and puppeteering for TV. His teacher, veteran puppeteer Michael Earl, who worked on “The Muppets” in the 1970s, compared his work to a young Jim Henson’s.

(Courtesy of Ammar Alsabban)

In Jeddah, Ammar crafted his own version of “The Muppets” and “Sesame Street.” He built puppets, including Afroot, a Yeti whom Ammar imagined had immigrated to Jeddah with his family from the Himalayas. He wrote scripts for his puppets, posted YouTube videos of his puppet shows, and sought work with hospitals, schools, and other community partners. Although he promoted a vision of edutainment analogous to what he had watched on TV – family friendly, educational, and inclusive – the initial reception was not promising. He said Saudis were “not into puppetry” at that time. It was still largely an unpopular genre of art in the kingdom, forcing him to create a market for his work from scratch. His first paid performance was at a birthday party. Still, Ammar earned around 280,000 Saudi riyals ($75,000) during the first eight months of his new career, a substantial sum of money at the time for this type of performing arts in the kingdom.

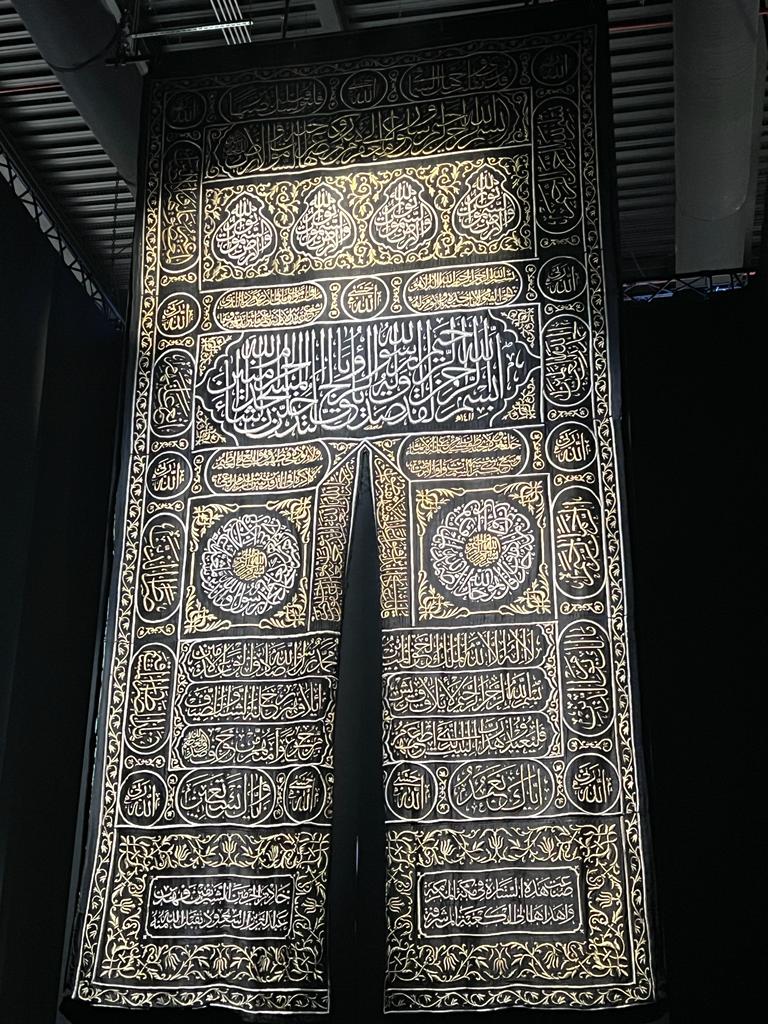

(Courtesy of Ammar Alsabban)

At the same time, Ammar’s videos, especially the ones featuring Afroot, caught fire on social media, helping him secure a job in 2015 with Bidaya Media in Abu Dhabi. There, he joined the reboot of “Iftah Ya Simsim,” the Arabic version of “Sesame Street” that was first broadcast from 1979-90 and that Ammar had watched as a child. As part of his training for the new position, he traveled to New York to study under Martin Robinson, one of the most gifted puppeteers on “Sesame Street.” Ammar earned the nickname “lefty” in New York from the “Sesame Street” puppet builders because he was the first left-handed puppeteer to use the Cookie Monster puppet. On “Iftah Ya Simsim,” Ammar served as the creative director, wrote scripts for six of the 100 episodes, and voiced multiple characters, including Gagur (Grover) and Ka’aki (Cookie Monster). This was challenging work: It required him to produce clear, positive, and educational messages in properly accented Arabic suitable for the entire Arab world. The shows also had to be humorous and retain the attention of the young audience. But the activities his parents once feared were useless were finally paying off. “Growing up watching ‘The Muppets’ and ‘Sesame Street’ religiously,” he observed in 2018, “gave me the advantage that I have now.” A year later he told Arab News that he was living his “childhood dream.”

(Courtesy of Ammar Alsabban)

However, the stress of working on “Iftah Ya Simsim” and living far from his family in Jeddah convinced Ammar not to renew his contract with Bidaya Media in 2019 and to return home to focus on freelance work in the kingdom. Five years earlier, he and a group of friends had pioneered “Mstdfr,” one of the first podcasts in Saudi Arabia. The show’s title came from dafoor, an Arabic word meaning something between a “nerd” and a “geek,” speaking to its offbeat approach and unique outlook. While devising a format for how to package “Mstdfr” and how it should sound to listeners, Ammar remembered listening to “Car Talk” – an American call-in radio program broadcast in Saudi Arabia by the U.S. Consulate in Jeddah. The show, which aired from 1977 to 2012, featured Tom and Ray Magliozzi, Italian American brothers who owned an auto repair shop in a suburb of Boston and dispensed advice to listeners about how to fix their cars. The core of the show was the banter between the Magliozzi brothers. On each episode, they made fun of one another and told jokes and humorous stories while interacting with listeners.

It was a perfect model for Ammar because “Car Talk” was an adult version of the edutainment that he had successfully produced for children using puppets. On “Mstdfr,” he and his partner and co-founder Rami Taibah borrowed the U.S. show’s formula but gave it a Saudi accent. Rather than advising their listeners about car repairs, they focused on Saudi Arabia and topics they and other young Saudis found interesting in their daily lives. They spoke to their audience in “Arablish,” a blend of English and Arabic, which many of their listeners also used – a choice that, like the show’s name, gave them authenticity. Ammar and his friends also used music and jokes, just as Tom and Ray Magliozzi did on “Car Talk,” to fill in gaps in conversation. By 2016, “Mstdfr” was one of the most popular podcasts in Saudi Arabia, with fans calling themselves “Mstdfri.”

As his first podcast began to take off, Ammar was already working on “Kartoon Karton,” a podcast he developed with Abdullah Rafaah. The two men, who worked together on “Iftah Ya Simsim” and shared an apartment in Abu Dhabi, spent hours discussing the storylines, characters, and production of their favorite cartoons. In 2017, they moved their conversations to a podcast, which found a passionate audience in Saudi Arabia and among the thousands of Saudis and other Gulf nationals living abroad. Those listeners became a tight-knit community, adopting the name “Karateen” (the Arabic plural of cartoon) and hosting their own online and in-person “Kartoon Karton” listening parties. They pressed Ammar and Abdullah to hold a live recording, and on the second anniversary of the show the two men organized an in-person event in Jeddah that was attended by more than a hundred people.

During the live recording of “Kartoon Karton,” fans were moved to find other people who, like Ammar, might be socially awkward and who shared his and Abdullah’s niche interest in cartoons. Many became close friends. At later events, Ammar heard stories about how the podcast had positively shaped the lives of listeners, including some who had been on the verge of suicide but, through the show, realized that they were not alone in the world and that there were others like them. “One of the biggest reasons for why we do what we do,” Ammar explained in an interview in 2023 “is that we don’t want people to feel lonely.”

By that time, Ammar’s various creative enterprises had taken off. He co-founded a podcast network with over 13 weekly podcasts, was selected as part of the inaugural cohort of the MiSK 2030 Leaders Program, wrote children’s stories, and forged a new partnership with U.S. creatives. On a panel at the Jeddah Book Fair in 2021, he befriended Ben Earl – a veteran cartoonist for Marvel, who had worked on “Deadly Neighborhood Spider-Man” and “Werewolf by Night.” Ammar and Ben agreed that there was an underserved global market for stories geared to children and young adults rooted in the culture and mythology of the Middle East. They thought a company serving this market with “Marvel-like content with a Middle-East flavor” could help to bridge gaps between societies, prompting them to form WeirdBunch Entertainment. Today, the studio has Saudi and U.S. funding and offices in Jeddah, New York, and Los Angeles. Its senior officers are Ammar and Ben, along with Keith Fay, who directed original series for the Cartoon Network from 2013 to 2022, and Abdullah Alsabban, Ammar’s older brother, who has held leadership positions in senior Saudi companies, such as Panda, one of the country’s most important supermarket chains.

(Courtesy of Ammar Alsabban)

Ammar wrote the inaugural project for the studio, “The Legend of Soloman,” the first Saudi family superhero story. Set in the kingdom in 2050, it follows Soloman, a rebellious 14 year old with a tense relationship with his father. He is a geologist and traditionalist who wants his son to master a 400-page manual before using his superhero powers to benefit society. Soloman has other ideas, and father and son must learn to work together to battle a dark curse. WeirdBunch Entertainment has already created a comic book version of “Legend of Soloman” in Arabic as well as a playable demo for a mobile game and intends to animate it as well, with versions available in English and Arabic. In the future, Ammar hopes the company will expand to telling stories not only from the Middle East but also from South Africa and other countries.

This follows the path of other Saudi creatives, such as Malik Nejer, the director of the Saudi animated series “Masameer,” whose most recent film, “Masameer Junior,” featured Ammar as a voice actor. Malik and his team have also partnered with Chinese and Saudi animators to bring “Ne Zha 2,” a blockbuster animated fantasy action-adventure film series, to Middle East screens in summer 2025. Because many Arab viewers are not familiar with Chinese mythology, Malik explained to Xinhua, he “matched each on-screen tribe with a distinct Arabic dialect” and searched for cultural parallels when concepts had no exact equivalent in the Arab world. Ultimately, the film that viewers will see in Arab theaters is, in Malik’s words, “Ne Zha 2” but “with a Saudi accent.”

These types of cross-cultural partnerships closely echo the principles that Ammar has promoted in his work along with how he, Malik, and other Saudi creatives define themselves and their place in the world today. Many of these Saudis imagine their world and express themselves in their art and other aspects of their life through collage. Ammar’s social media avatar, in which he pulls away his thobe to reveal a blue shirt imprinted with the red letter “S,” is in homage to the iconic image of Superman transforming from his alter ego Clark Kent into a superhero. “Don’t follow your passions,” Ammar told AGSI. “Instead, identify your purpose and utilize your passions to help you achieve it.” Ammar has done so with great passion for over a decade and emerged as one of Saudi Arabia’s most dynamic creative actors.

The views represented herein are the author's or speaker's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of AGSI, its staff, or its board of directors.