Venezuela, Trump, and Implications for OPEC’s Middle Eastern Core

A founding member of OPEC is now effectively under external control, raising questions about sovereignty, influence, and the resilience of producer-led market management.

The United States’ intervention in Venezuela puts the country at the center of global oil politics and could pose a challenge to the ability of OPEC to manage the oil market in a new energy order being crafted by President Donald J. Trump. Saudi Arabia and the other Gulf oil producers in OPEC have not commented on the latest developments in Caracas after U.S. forces raided the presidential palace on January 3 and captured President Nicolás Maduro and his wife, who have been indicted in a U.S. federal court on charges including narco-terrorism.

In the few days since that dramatic raid, the narrative in Washington has changed with Trump stating publicly that the United States intends to run Venezuela and take direct control of Venezuelan oil exports and revenue “indefinitely.” During a January 9 meeting with CEOs and senior executives of U.S. and international oil companies, Trump said Venezuela would hand over 50 million barrels of its crude to be refined or marketed by the United States “immediately.” This might have an impact on near-term oil supplies at a time when the market is well supplied, though much of the extra heavy Venezuelan oil is likely to be taken by U.S. refineries for blending with the lighter grades produced domestically. “We have the refining capacity – was actually based very much on the Venezuelan oil, which is a heavy oil, very good oil, great oil,” Trump said during the televised meeting. He also urged the international oil companies to help rehabilitate the Venezuelan oil industry that he said had been mismanaged and would require $100 billion in investments to achieve its true potential.

Global oil prices did not react to the developments in Venezuela. There might be longer term implications for supply, but few experts expect an immediate surge in Venezuelan oil production given the dilapidated state of the Venezuelan oil industry’s infrastructure, the need for a new fiscal regime and hydrocarbon law, and concerns about continued insecurity – issues raised by some executives during the meeting at the White House. Brent crude oil was trading between $61 per barrel and $63/bbl, roughly at the same level at the close of business in December 2025, in the days following the intervention in Venezuela. They rose sharply on January 13 to trade above $65/bbl on market fears of disruption to Iranian oil supplies amid a wave of nationwide protests that began at the end of December.

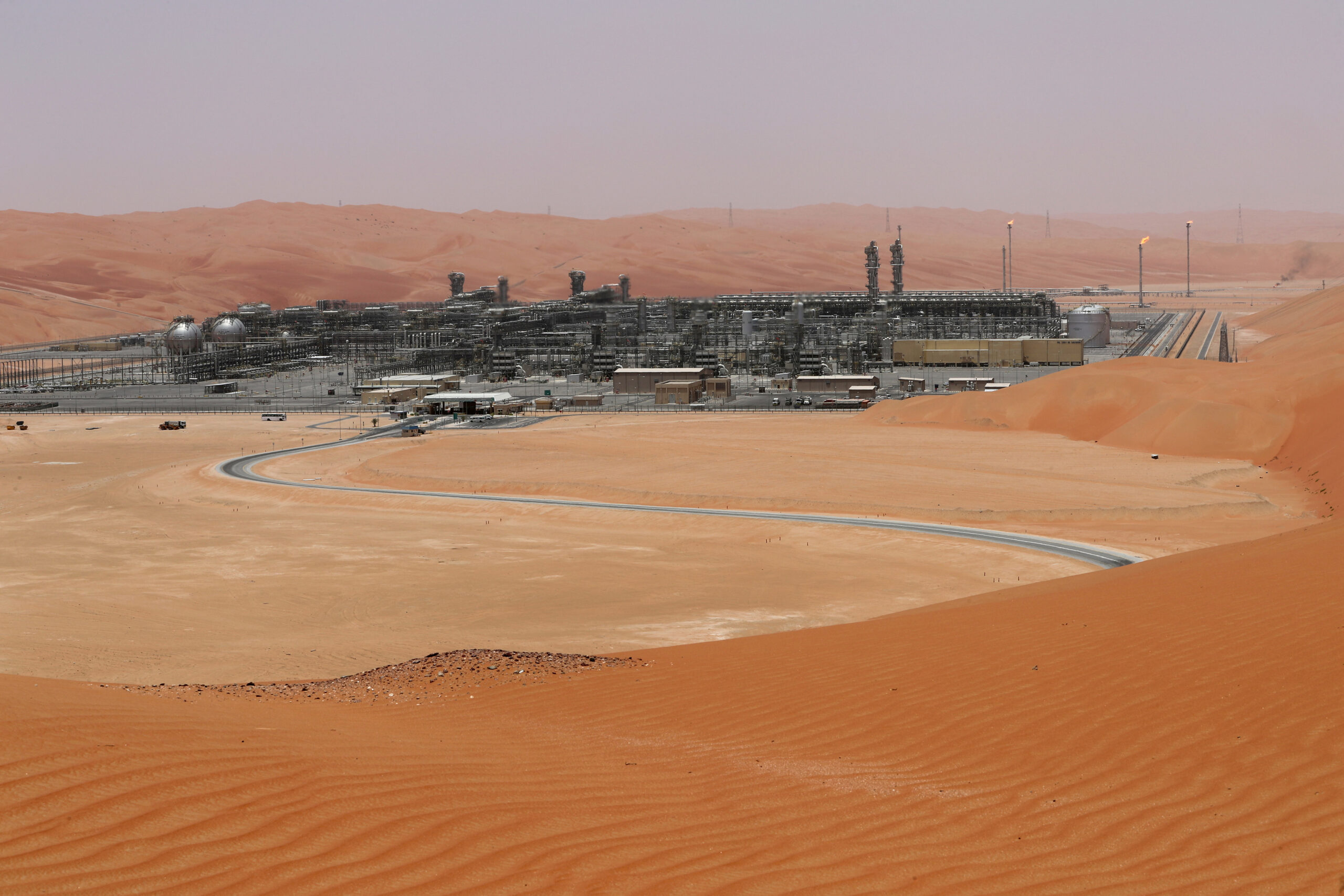

From a narrow market perspective, the implications for OPEC are modest in the short term. Venezuela’s output, hovering just below 1 million barrels per day (around 1% of global supply), remains far below its late-1990s peak of nearly 3.5 mb/d. This is a fraction of what the country could produce given its massive resource base, estimated at 303 billion barrels, the largest in the world, though not all of it is commercially viable. On paper, Venezuela’s oil reserves exceed Saudi Arabia’s 267 billion barrels, but Saudi Arabia has capacity to produce more than 10 times as much oil as Venezuela thanks to a stable government and a well-run state oil company in Saudi Aramco. The United States, with 44 billion barrels of reserves, is today the world’s largest oil producer due to the surge in shale oil production that allowed it to overtake Saudi Arabia and Russia, with current U.S. oil production estimated at over 20 mb/d.

In Venezuela, decades of underinvestment, infrastructure decay, and institutional collapse at state oil company Petróleos de Venezuela, known as PDVSA, as well as more recent U.S. sanctions mean that even under optimistic assumptions production growth would be slow, capital intensive, and measured in years rather than months. This helps explain why oil prices have remained relatively calm, despite the geopolitical drama, and why OPEC has made no official comment on the developments.

What matters for OPEC, and for the market, is not reserves in the ground but barrels that can be produced and marketed effectively. Venezuela has had to rely on oil swaps with Iran, another OPEC member struggling with a collapsing economy due to sanctions, and on China, which receives some Venezuelan oil as debt repayment.

As one of OPEC’s five founding members at a time when its production was on the rise, Venezuela was able to shape policy decisions within the group. That influence waned after the late Hugo Chavez took over management of the oil sector from PDVSA, firing hundreds of employees and squeezing the oil giant’s revenue to fund his populist agenda as Venezuela’s president. Production plummeted further after a 2002-03 strike by PDVSA oil workers crippled the industry. Oil production fell below 500,000 b/d, and exports were severely disrupted. Thousands of employees were fired or left the country. Even after production recovered in subsequent years, the industry never regained its prestrike technical depth, as the government’s take increased.

In 2007, Chavez expelled major U.S. oil companies, including ExxonMobil and ConocoPhillips, and seized their assets, for which the companies are still awaiting billions of dollars in compensation. Chevron was the only major U.S. oil company that stayed, operating under a special U.S. license, and could ramp up production in the short term.

While major oil companies often operate in risky environments, they require guarantees of returns on their investments in a stable fiscal environment. Both ExxonMobil and Chevron are considering investments in Iraq’s energy sector, which also faces an unpredictable political future given the current postelection paralysis but provides lower cost and higher quality crude than Venezuela’s extra heavy oil.

Tackling methane emissions from Venezuela’s oil and gas operations would be an additional cost to any potential investor. The International Energy Agency noted in the “Latin America Energy Outlook 2023” that “the methane emissions intensity of oil and gas operations in Venezuela is five-times the world average, and their flaring intensity is over seven-times higher the global average.” Although the environmental impact of methane emissions may not be of much concern to the current U.S. administration, it is relevant to the multinational oil companies. At the December 2023 COP28 climate summit in Dubai more than 50 oil and gas companies, including the U.S. majors, pledged to reduce methane emissions from their operations to near zero by 2030. Methane is a powerful greenhouse gas that traps heat close to the earth’s surface. Venezuela is not a signatory to the Global Methane Pledge.

ExxonMobil’s CEO, Darren Woods, was virtually alone among the executives to argue that Venezuela was not currently an attractive investment prospect. He told the U.S. president, “We first got into Venezuela back in 1940s. We’ve had our assets seized there twice. And so, you can imagine to re-enter a third time would require some pretty significant changes from what we’ve historically seen here … If we look at the legal and commercial constructs – frameworks – in place today in Venezuela, today it’s uninvestable. And so significant changes have to be made,” including to the country’s hydrocarbon law and its legal system, he added.

For decades prior to the Chavez presidency, PDVSA acted as a state within a state, with the head of the company enjoying greater power than the minister of energy. Such was PDVSA’s influence that one minister had compared it to “an elephant in a swimming pool” because of the ripple effect its decisions had on the country’s economy, according to a section in the book “Oil Leaders” by former senior Saudi oil advisor Ibrahim AlMuhanna.

As its oil production slumped so did Venezuela’s influence in OPEC. Today, effective market management rests with the Gulf states – led by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates – alongside Russia within the OPEC+ alliance. That concentration of influence has delivered stability, but it also means Arab producers are acutely sensitive to any precedent that weakens producer sovereignty or normalizes external intervention in oil-exporting states.

Another dimension that matters for the Middle East is the question of influence within OPEC and OPEC+. With the United States now asserting de facto control over Venezuelan oil sales and revenue, will that translate into indirect influence on OPEC or OPEC+ deliberations? Could the United States eventually push for Venezuela’s withdrawal from the organization? It is far too early to answer these questions, but they are ones that Gulf producers and other members will no doubt be discussing behind closed doors.

At present, Venezuela is exempt from OPEC+ output quotas, and the United States would certainly not allow production to be dictated by the Saudi- and Russian-led alliance even if production were to increase. There is a consensus among experts that it will take years or even decades to restore Venezuelan production beyond the 2025 average of 930,000 b/d.

Ivan Sandrea, a Venezuelan energy expert and a former head of oil supply at OPEC, wrote in a LinkedIn post that he had reviewed crude oil production data from Iran, Iraq, Algeria, Libya, and Venezuela – all members of OPEC – over 1970-75 and examined how long it took each to recover peak production. All five have suffered from output declines either because of geology, lack of investment in new capacity, internal strife, or sanctions. He noted that the period was chosen specifically because “it marked the peak of Venezuelan production, preceded the Iranian Revolution, and came before major regime change, conflict, and structural disruption across several OPEC producers.” (It was also during this period that OPEC wielded its oil weapon with the 1973 oil embargo, which led to the rise of North Sea oil and a U.S. quest for energy independence at a time when the Middle East was one of its biggest suppliers.)

In an accompanying chart, Sandrea showed that recovery is generally slow, uneven, and rarely linear, and that geology is not the primary constraint. Iran, Libya, and Algeria needed 20 years to recover production, while Iran and Venezuela never fully recovered. Iran produced 3.3 mb/d of crude oil in November 2025, according to secondary source estimates cited by OPEC, which is roughly half what it produced at its peak in the mid-1970s and far below current capacity.

Sandrea pointed out that Venezuela is the most extreme case with production today at 20% of its peak level. This, he wrote, reflects “profound destruction of capacity rather than resource depletion.” Iraq, by contrast, managed to restore and significantly expand production within roughly a decade following the ouster of Saddam Hussein in 2003. “For Venezuela, the challenge – and the opportunity – is clear,” he wrote, adding that it would likely take more than 10 years to restore production in Venezuela, assuming discipline and sustained execution. “Expectations of a rapid production surge should therefore be tempered accordingly.”

The U.S. Energy Information Administration admitted as such in a February 2024 analysis of Venezuela’s oil sector. In the report, the EIA estimated that Venezuela’s total energy production declined by an average 8.2% between 2011 and 2021 due to what it said was “government mismanagement, international sanctions, and the country’s economic crisis.” As a result, it expects crude oil output growth to be limited even after the lifting of U.S. sanctions.

Should U.S. firms return to Venezuela, they would find a sector hollowed out by years of underinvestment, operational decay, and institutional dysfunction. For OPEC’s Middle Eastern core, the significance of Venezuela’s upheaval lies less in near-term supply than in the precedent it sets. A founding member of the organization is now effectively under external control, raising questions about sovereignty, influence, and the resilience of producer-led market management.

The views represented herein are the author's or speaker's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of AGSI, its staff, or its board of directors.