The MENA Power Transformation: Meeting Unprecedented Demand

The Middle East and North Africa will experience an unprecedented level of energy demand between now and 2035, pushing Gulf countries to find new ways to meet that demand.

Demand for electricity in the Middle East and North Africa is set to rise 50% by 2035, an unprecedented level of growth that will be driven by a swelling population, urbanization, and a surge in demand for air conditioning and desalination, according to a new report by the International Energy Agency. This means an additional 760 terawatt-hours needs to be added to existing power generation capacity in less than a decade.

The IEA noted that this is the equivalent of adding the current demand of Germany and Spain combined, a challenging task for a region already grappling with extreme heat and water scarcity due to “accelerating climate pressures.” In the report, “The Future of Electricity in the Middle East and North Africa,” the IEA estimated that, between now and 2035, cooling and desalination together will account for 40% of projected growth in electricity demand in the region. Other key drivers are industrial growth, the electrification of the transportation sector, urbanization, and the new digital economy.

“Demand for electricity is surging across the Middle East and North Africa, driven by the rapidly rising need for air conditioning and water desalination in a heat- and water-stressed region with growing populations and economies,” IEA Executive Director Fatih Birol said in a statement about the findings of the report. “To meet this demand, power capacity over the next 10 years is set to expand by over 300 gigawatts, the equivalent of three times Saudi Arabia’s current total generation capacity,” he added.

One-quarter of households in the Middle East and North Africa currently have air conditioning, compared with near-universal saturation in the Gulf states. As incomes rise and temperatures climb, cooling alone could add 175 terawatt-hours of new demand, nearly one-quarter of the projected growth.

Water scarcity compounds the challenge. The Gulf accounts for 70% of today’s desalination capacity, but demand for fresh water is rising across the region. The IEA expects electricity use for desalination to triple by 2035, adding more than 100 terawatt-hours.

Electricity demand in the region has been on the rise even as the major economies have become more service oriented. The IEA estimates that electricity demand tripled between 2000 and 2024, increasing to 1,000 terawatt-hours, making it the third-largest contributor to global electricity demand growth after China and India.

Much of this high level of demand growth is due to subsidies and the absence of effective energy efficiency measures in all but a handful of countries. The IEA estimates that over the past decade, the region has spent an average $250 billion per year on fossil fuel subsidies with electricity subsidies alone accounting for more than $80 billion. These fuel subsidies are a drain on the economy and make power generation uneconomic in some countries because power suppliers cannot cover their operating costs. Subsidy reforms have been introduced by some countries, including Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Egypt, although rates generally remain below reference prices. Subsidies are a particular burden on countries that are net importers, including Egypt and Kuwait. Furthermore, the region’s economies remain energy intensive, despite a decline in the contribution of the industrial sector to gross domestic product. This has contributed to a rise in carbon dioxide emissions – the CO2 intensity of GDP rose by 11% between 1990 and 2023, compared to a global average decline of 37% over the same period, the report noted.

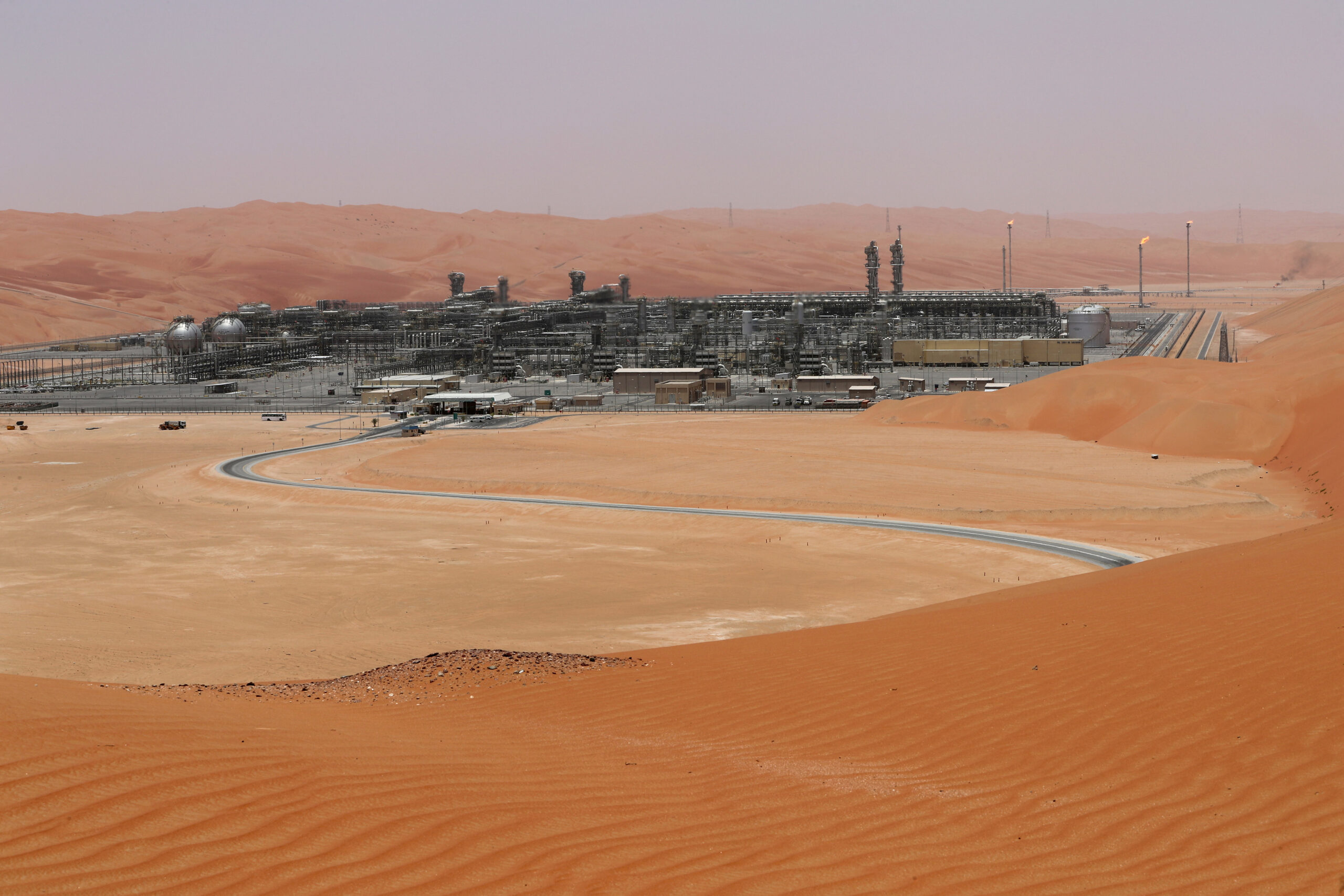

Historically, countries in the region relied on oil and natural gas for power generation, but that mix of fuels is shifting as more renewables capacity comes online. In 2023, fossil fuels accounted for 90% of generation, with oil alone making up one-fifth. By 2035, oil’s share will fall to just 5% as it is displaced by gas and renewable energy. Installed renewable capacity, just 6% of the total in 2024, could rise to nearly 300 gigawatts by 2035 to make up one-quarter of all generation. Solar and wind will dominate, accounting for 60% of all new capacity additions.

The shift is not simply about climate commitments. For Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and Kuwait, reducing the amount of oil that is burned to generate electricity frees up crude for exportation. If oil displacement falters, the IEA estimates regional economies could forfeit $80 billion in export revenue and face $20 billion in import bills.

The scale of change is huge, and progress will be uneven. Gulf Cooperation Council states, with substantial resources and favorable investment environments, are advancing modern grids and large-scale renewables. In contrast, countries with outdated infrastructure and weaker economies may face challenges in upgrading grids or drawing major investments. “A resilient grid is the backbone of a reliable clean power system,” the IEA noted. Yet many countries still face high transmission losses and inadequate infrastructure.

The IEA projects power sector investment to grow by 50%, from $40 billion in 2023 to $60 billion in 2035, with half dedicated to transmission and distribution.

Battery energy storage is also expected to play a growing role, with capacity rising from barely 1 GW to 7 GW by 2035. Egypt, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia are leading early adoption, with the kingdom targeting 48 gigawatt-hours of storage by 2030.

Two emerging sectors could reshape the regional electricity story: green hydrogen and data centers. If announced hydrogen targets materialize, the sector could become the largest source of new demand as electrolyzers needed for production of green hydrogen require a vast amount of renewable energy. Yet progress has been slow. Saudi Arabia’s flagship Neom project, due online in 2027, remains the most advanced, but cost barriers and difficulties in securing firm buyers have slowed momentum across the region. Meanwhile, data centers are multiplying as the Middle East is carving out a role as a digital hub. Gigawatt-scale projects are being planned in Saudi Arabia and the UAE, though the full impact on electricity demand remains unknown.

Saudi Arabia has set an ambitious target to displace oil in power generation. Total power generation capacity is set to double from 100 GW to 200 GW by 2035. The kingdom plans to eliminate oil from its generation mix by 2030, replacing it with a 50:50 balance of gas and renewables.

Saudi Arabia is targeting 130 GW of renewables by 2030. Even the IEA’s more cautious projection of “nearly 100 GW” would give the kingdom one-third of the region’s total renewable buildout. The stakes are enormous. Failure to displace liquids could cost Riyadh $150 billion in lost oil export revenue over the next decade. But, if successful, Saudi Arabia would set the template for the wider region – proving that even an economy long defined by oil dependence can pivot to a cleaner, more diversified power system.

Nuclear energy is another potential source of power supply for the Middle East and North Africa. There are five nuclear reactors operational in the region, including four in the UAE, that have been commissioned in the past five years, adding to the existing nuclear power station in Iran. A new nuclear power station is under construction in Egypt and one in Iran, while the UAE is considering an expansion of its nuclear capacity. Saudi Arabia is also advancing plans for its first nuclear unit. These proposed projects would triple nuclear capacity to 19 GW by 2035.

The next 10 years will determine whether the Middle East and North Africa can balance soaring electricity demand with sustainable supply. Cooling, desalination, and urban growth will keep pressure on systems already stretched thin. Oil’s retreat from the power mix creates both risk and opportunity. And while the Gulf states are well positioned to lead, others risk falling behind.

Electricity demand in the Middle East is rising at a pace the world has never seen before. How the region responds will shape not only its economic future but also the global energy landscape.

The views represented herein are the author's or speaker's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of AGSI, its staff, or its board of directors.